Excel.vba.for.dummies

- 1. Excel VBA Programming FOR DUMmIES ‰ by John Walkenbach

- 3. Excel VBA Programming FOR DUMmIES ‰ by John Walkenbach

- 4. Excel VBA Programming For Dummies® Published by Wiley Publishing, Inc. 111 River Street Hoboken, NJ 07030-5774 Copyright © 2004 by Wiley Publishing, Inc., Indianapolis, Indiana Published by Wiley Publishing, Inc., Indianapolis, Indiana Published simultaneously in Canada No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except as permitted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permis- sion of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Legal Department, Wiley Publishing, Inc., 10475 Crosspoint Blvd., Indianapolis, IN 46256, (317) 572-3447, fax (317) 572-4355, e-mail: brandreview@ wiley.com. Trademarks: Wiley, the Wiley Publishing logo, For Dummies, the Dummies Man logo, A Reference for the Rest of Us!, The Dummies Way, Dummies Daily, The Fun and Easy Way, Dummies.com, and related trade dress are trademarks or registered trademarks of John Wiley & Sons, Inc. and/or its affiliates in the United States and other countries, and may not be used without written permission. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. Wiley Publishing, Inc., is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book. LIMIT OF LIABILITY/DISCLAIMER OF WARRANTY: THE PUBLISHER AND THE AUTHOR MAKE NO REP- RESENTATIONS OR WARRANTIES WITH RESPECT TO THE ACCURACY OR COMPLETENESS OF THE CONTENTS OF THIS WORK AND SPECIFICALLY DISCLAIM ALL WARRANTIES, INCLUDING WITHOUT LIMITATION WARRANTIES OF FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. NO WARRANTY MAY BE CRE- ATED OR EXTENDED BY SALES OR PROMOTIONAL MATERIALS. THE ADVICE AND STRATEGIES CON- TAINED HEREIN MAY NOT BE SUITABLE FOR EVERY SITUATION. THIS WORK IS SOLD WITH THE UNDERSTANDING THAT THE PUBLISHER IS NOT ENGAGED IN RENDERING LEGAL, ACCOUNTING, OR OTHER PROFESSIONAL SERVICES. IF PROFESSIONAL ASSISTANCE IS REQUIRED, THE SERVICES OF A COMPETENT PROFESSIONAL PERSON SHOULD BE SOUGHT. NEITHER THE PUBLISHER NOR THE AUTHOR SHALL BE LIABLE FOR DAMAGES ARISING HEREFROM. THE FACT THAT AN ORGANIZATION OR WEBSITE IS REFERRED TO IN THIS WORK AS A CITATION AND/OR A POTENTIAL SOURCE OF FUR- THER INFORMATION DOES NOT MEAN THAT THE AUTHOR OR THE PUBLISHER ENDORSES THE INFORMATION THE ORGANIZATION OR WEBSITE MAY PROVIDE OR RECOMMENDATIONS IT MAY MAKE. FURTHER, READERS SHOULD BE AWARE THAT INTERNET WEBSITES LISTED IN THIS WORK MAY HAVE CHANGED OR DISAPPEARED BETWEEN WHEN THIS WORK WAS WRITTEN AND WHEN IT IS READ. For general information on our other products and services or to obtain technical support, please contact our Customer Care Department within the U.S. at 800-762-2974, outside the U.S. at 317-572-3993, or fax 317-572-4002. Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books. Library of Congress Control Number: 2004107892 ISBN: 0-7645-7412-4 Manufactured in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 1B/QV/QY/QU/IN

- 5. About the Author John Walkenbach is the author of more than 40 spreadsheet books and lives in southern Arizona. Visit his Web site at http://j-walk.com. Author’s Acknowledgments Thanks to all of the talented people at Wiley Publishing for making it so easy to write these books. Special thanks to Dick Kusleika, the technical editor for this book. Dick uncovered quite a few errors and set me straight on a few things.

- 6. Publisher’s Acknowledgments We’re proud of this book; please send us your comments through our online registration form located at www.dummies.com/register/. Some of the people who helped bring this book to market include the following: Acquisitions, Editorial, and Composition Media Development Project Coordinator: Adrienne Martinez Project Editor: Beth Taylor Layout and Graphics: Amanda Carter, Executive Editor: Greg Croy Andrea Dahl, Lauren Goddard, Copy Editor: Tonya Cupp Stephanie D. Jumper, Michael Kruzil, Lynsey Osborn, Jacque Roth Technical Editor: Dick Kusleika Proofreaders: Laura Albert, Editorial Manager: Leah Cameron TECHBOOKS Production Services Media Development Specialist: Kit Malone Indexer: TECHBOOKS Production Services Media Development Manager: Laura VanWinkle Media Development Supervisor: Richard Graves Editorial Assistant: Amanda Foxworth Cartoons: Rich Tennant, www.the5thwave.com Publishing and Editorial for Technology Dummies Richard Swadley, Vice President and Executive Group Publisher Andy Cummings, Vice President and Publisher Mary Bednarek, Executive Acquisitions Director Mary C. Corder, Editorial Director Publishing for Consumer Dummies Diane Graves Steele, Vice President and Publisher Joyce Pepple, Acquisitions Director Composition Services Gerry Fahey, Vice President of Production Services Debbie Stailey, Director of Composition Services

- 7. Contents at a Glance Introduction .................................................................1 Part I: Introducing VBA ................................................9 Chapter 1: What Is VBA?..................................................................................................11 Chapter 2: Jumping Right In............................................................................................21 Part II: How VBA Works with Excel..............................31 Chapter 3: Introducing the Visual Basic Editor ............................................................33 Chapter 4: Introducing the Excel Object Model ...........................................................51 Chapter 5: VBA Sub and Function Procedures .............................................................63 Chapter 6: Using the Excel Macro Recorder .................................................................75 Part III: Programming Concepts...................................87 Chapter 7: Essential VBA Language Elements ..............................................................89 Chapter 8: Working with Range Objects......................................................................107 Chapter 9: Using VBA and Worksheet Functions .......................................................119 Chapter 10: Controlling Program Flow and Making Decisions .................................133 Chapter 11: Automatic Procedures and Events..........................................................151 Chapter 12: Error-Handling Techniques ......................................................................171 Chapter 13: Bug Extermination Techniques ...............................................................185 Chapter 14: VBA Programming Examples ...................................................................195 Part IV: Developing Custom Dialog Boxes ...................213 Chapter 15: Custom Dialog Box Alternatives..............................................................215 Chapter 16: Custom Dialog Box Basics........................................................................231 Chapter 17: Using Dialog Box Controls........................................................................247 Chapter 18: UserForm Techniques and Tricks ...........................................................265 Part V: Creating Custom Toolbars and Menus ..............287 Chapter 19: Customizing the Excel Toolbars..............................................................289 Chapter 20: When the Normal Excel Menus Aren’t Good Enough ...........................307 Part VI: Putting It All Together..................................323 Chapter 21: Creating Worksheet Functions — and Living to Tell about It ..............325 Chapter 22: Creating Excel Add-Ins..............................................................................339 Chapter 23: Interacting with Other Office Applications............................................351

- 8. Part VII: The Part of Tens ..........................................363 Chapter 24: Ten VBA Questions (And Answers) ........................................................365 Chapter 25: (Almost) Ten Excel Resources.................................................................369 Index .......................................................................373

- 9. Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................1 Is This the Right Book?....................................................................................1 So You Want to Be a Programmer . . . ............................................................2 Why Bother? .....................................................................................................3 What I Assume about You ...............................................................................3 Obligatory Typographical Conventions Section ..........................................4 Check Your Security Settings..........................................................................5 How This Book Is Organized...........................................................................5 Part I: Introducing VBA ..........................................................................6 Part II: How VBA Works with Excel ......................................................6 Part III: Programming Concepts............................................................6 Part IV: Developing Custom Dialog Boxes...........................................6 Part V: Creating Custom Toolbars and Menus....................................6 Part VI: Putting It All Together..............................................................6 Part VII: The Part of Tens ......................................................................7 Marginal Icons ..................................................................................................7 Get the Sample Files.........................................................................................8 Now What? ........................................................................................................8 Part I: Introducing VBA .................................................9 Chapter 1: What Is VBA? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .11 Okay, So What Is VBA?...................................................................................11 What Can You Do with VBA?.........................................................................12 Inserting a text string...........................................................................13 Automating a task you perform frequently.......................................13 Automating repetitive operations ......................................................13 Creating a custom command ..............................................................13 Creating a custom toolbar button......................................................13 Creating a custom menu command ...................................................14 Creating a simplified front end ...........................................................14 Developing new worksheet functions................................................14 Creating complete, macro-driven applications ................................14 Creating custom add-ins for Excel .....................................................14 Advantages and Disadvantages of VBA.......................................................15 VBA advantages....................................................................................15 VBA disadvantages...............................................................................15 VBA in a Nutshell ...........................................................................................16 An Excursion into Versions...........................................................................18

- 10. viii Excel VBA Programming For Dummies Chapter 2: Jumping Right In . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .21 What You’ll Be Doing .....................................................................................21 Taking the First Steps ....................................................................................22 Recording the Macro .....................................................................................23 Testing the Macro ..........................................................................................24 Examining the Macro .....................................................................................25 Modifying the Macro......................................................................................28 More about the ConvertFormulas Macro....................................................29 Part II: How VBA Works with Excel ..............................31 Chapter 3: Introducing the Visual Basic Editor . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .33 What Is the Visual Basic Editor? ..................................................................33 Activating the VBE ...............................................................................33 Understanding VBE components .......................................................34 Working with the Project Explorer...............................................................36 Adding a new VBA module..................................................................36 Removing a VBA module .....................................................................37 Exporting and importing objects .......................................................37 Working with a Code Window.......................................................................38 Minimizing and maximizing windows ................................................38 Creating a module ................................................................................39 Getting VBA code into a module ........................................................39 Entering code directly .........................................................................40 Using the macro recorder ...................................................................42 Copying VBA code................................................................................44 Customizing the VBA Environment .............................................................44 Using the Editor tab .............................................................................45 Using the Editor Format tab................................................................47 Using the General tab ..........................................................................48 Using the Docking tab..........................................................................48 Chapter 4: Introducing the Excel Object Model . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .51 Excel Is an Object? .........................................................................................52 Climbing the Object Hierarchy.....................................................................52 Wrapping Your Mind around Collections....................................................53 Referring to Objects.......................................................................................54 Navigating through the hierarchy ......................................................55 Simplifying object references..............................................................56 Diving into Object Properties and Methods ...............................................56 Object properties .................................................................................58 Object methods ....................................................................................59 Object events ........................................................................................60 Finding Out More ...........................................................................................60 Using VBA’s Help system .....................................................................60 Using the Object Browser....................................................................61

- 11. Table of Contents ix Chapter 5: VBA Sub and Function Procedures . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .63 Subs versus Functions...................................................................................63 Looking at Sub procedures .................................................................64 Looking at Function procedures.........................................................64 Naming Subs and Functions................................................................65 Executing Sub Procedures ............................................................................65 Executing the Sub procedure directly ...............................................67 Executing the procedure from the Macro dialog box ......................68 Executing a macro using a shortcut key ...........................................68 Executing the procedure from a button or shape ............................70 Executing the procedure from another procedure ..........................71 Executing Function Procedures ...................................................................72 Calling the function from a Sub procedure .......................................72 Calling a function from a worksheet formula....................................73 Chapter 6: Using the Excel Macro Recorder . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .75 Is It Live or Is It VBA?.....................................................................................75 Recording Basics............................................................................................76 Preparing to Record.......................................................................................78 Relative or Absolute?.....................................................................................78 Recording in absolute mode ...............................................................78 Recording in relative mode .................................................................79 What Gets Recorded? ....................................................................................81 Recording Options .........................................................................................82 Macro name...........................................................................................83 Shortcut key ..........................................................................................83 Store Macro In.......................................................................................83 Description............................................................................................83 Is This Thing Efficient? ..................................................................................84 Part III: Programming Concepts ...................................87 Chapter 7: Essential VBA Language Elements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .89 Using Comments in Your VBA Code ............................................................89 Using Variables, Constants, and Data Types ..............................................91 Understanding variables .....................................................................91 What are VBA’s data types?.................................................................92 Declaring and scoping variables ........................................................93 Working with constants .......................................................................98 Working with strings ..........................................................................100 Working with dates.............................................................................100 Using Assignment Statements ....................................................................101 Assignment statement examples......................................................102 About that equal sign.........................................................................102 Other operators..................................................................................102

- 12. x Excel VBA Programming For Dummies Working with Arrays ....................................................................................104 Declaring arrays .................................................................................104 Multidimensional arrays....................................................................105 Dynamic Arrays ..................................................................................105 Using Labels..................................................................................................106 Chapter 8: Working with Range Objects . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .107 A Quick Review.............................................................................................107 Other Ways to Refer to a Range .................................................................108 The Cells property .............................................................................109 The Offset property ...........................................................................110 Referring to entire columns and rows .............................................110 Some Useful Range Object Properties.......................................................111 The Value property ............................................................................111 The Text property ..............................................................................112 The Count property ...........................................................................112 The Column and Row properties .....................................................112 The Address property........................................................................113 The HasFormula property .................................................................113 The Font property ..............................................................................114 The Interior property.........................................................................114 The Formula property .......................................................................115 The NumberFormat property ...........................................................115 Some Useful Range Object Methods..........................................................116 The Select method .............................................................................116 The Copy and Paste methods...........................................................116 The Clear method...............................................................................117 The Delete method.............................................................................117 Chapter 9: Using VBA and Worksheet Functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .119 What Is a Function?......................................................................................119 Using VBA Functions ...................................................................................120 VBA function examples......................................................................120 VBA functions that do more than return a value ...........................122 Discovering VBA functions ...............................................................123 Using Worksheet Functions in VBA ...........................................................126 Worksheet function examples ..........................................................127 Entering worksheet functions...........................................................129 More about Using Worksheet Functions ...................................................130 Using Custom Functions .............................................................................131 Chapter 10: Controlling Program Flow and Making Decisions . . . . .133 Going with the Flow, Dude ..........................................................................133 The GoTo Statement ....................................................................................134 Decisions, decisions...........................................................................135 The If-Then structure .........................................................................135 The Select Case structure .................................................................140

- 13. Table of Contents xi Knocking Your Code for a Loop .................................................................143 For-Next loops.....................................................................................144 Do-While loop .....................................................................................147 Do-Until loop .......................................................................................148 Looping through a Collection .....................................................................149 Chapter 11: Automatic Procedures and Events . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .151 Preparing for the Big Event.........................................................................151 Are events useful? ..............................................................................154 Programming event-handler procedures ........................................154 Where Does the VBA Code Go? ..................................................................155 Writing an Event-Handler Procedure .........................................................156 Introductory Examples................................................................................157 The Open event for a workbook.......................................................157 The BeforeClose event for a workbook ...........................................159 The BeforeSave event for a workbook.............................................160 Examples of Activation Events ...................................................................161 Activate and Deactivate events in a sheet ......................................161 Activate and Deactivate events in a workbook ..............................161 Workbook activation events .............................................................162 Other Worksheet-Related Events ...............................................................163 The BeforeDoubleClick event ...........................................................163 The BeforeRightClick event ..............................................................163 The Change event...............................................................................164 Events Not Associated with Objects .........................................................166 The OnTime event..............................................................................167 Keypress events..................................................................................168 Chapter 12: Error-Handling Techniques . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .171 Types of Errors .............................................................................................171 An Erroneous Example ................................................................................172 The macro’s not quite perfect ..........................................................172 The macro is still not perfect............................................................174 Is the macro perfect yet?...................................................................174 Giving up on perfection .....................................................................176 Handling Errors Another Way.....................................................................176 Revisiting the EnterSquareRoot procedure ...................................176 About the On Error statement ..........................................................177 Handling Errors: The Details ......................................................................178 Resuming after an error.....................................................................178 Error handling in a nutshell ..............................................................180 Knowing when to ignore errors ........................................................180 Identifying specific errors .................................................................181 An Intentional Error .....................................................................................182 Chapter 13: Bug Extermination Techniques . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .185 Species of Bugs.............................................................................................185 Identifying Bugs............................................................................................186

- 14. xii Excel VBA Programming For Dummies Debugging Techniques ................................................................................187 Examining your code .........................................................................187 Using the MsgBox function ...............................................................187 Inserting Debug.Print statements ....................................................189 Using the VBA debugger....................................................................189 About the Debugger.....................................................................................189 Setting breakpoints in your code .....................................................189 Using the Watch window ...................................................................192 Bug Reduction Tips......................................................................................194 Chapter 14: VBA Programming Examples . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .195 Working with Ranges ...................................................................................195 Copying a range ..................................................................................196 Copying a variable-sized range.........................................................197 Selecting to the end of a row or column..........................................198 Selecting a row or column.................................................................199 Moving a range ...................................................................................199 Looping through a range efficiently.................................................200 Prompting for a cell value .................................................................201 Determining the selection type .......................................................202 Identifying a multiple selection ........................................................203 Changing Excel Settings ..............................................................................203 Changing Boolean settings................................................................204 Changing non-Boolean settings ........................................................204 Working with Charts ....................................................................................205 Modifying the chart type...................................................................205 Looping through the ChartObjects collection................................206 Modifying properties .........................................................................206 Applying chart formatting.................................................................207 VBA Speed Tips ............................................................................................207 Turning off screen updating..............................................................208 Turning off automatic calculation ....................................................208 Eliminating those pesky alert messages .........................................209 Simplifying object references............................................................209 Declaring variable types....................................................................210 Using the With-End With structure ..................................................211 Part IV: Developing Custom Dialog Boxes ....................213 Chapter 15: Custom Dialog Box Alternatives . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .215 Why Create Dialog Boxes? ..........................................................................215 The MsgBox Function ..................................................................................216 Displaying a simple message box.....................................................216 Getting a response from a message box..........................................217 Customizing message boxes .............................................................218

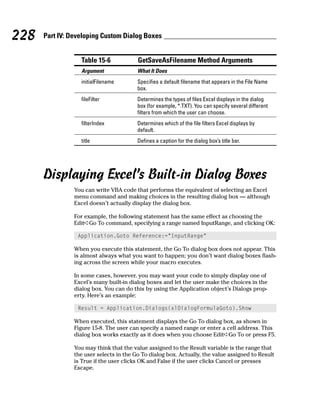

- 15. Table of Contents xiii The InputBox Function................................................................................221 InputBox syntax..................................................................................221 An InputBox example.........................................................................221 The GetOpenFilename Method...................................................................223 The syntax...........................................................................................223 A GetOpenFilename example............................................................224 Selecting multiple files.......................................................................226 The GetSaveAsFilename Method ...............................................................227 Displaying Excel’s Built-in Dialog Boxes....................................................228 Chapter 16: Custom Dialog Box Basics . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .231 Knowing When to Use a Custom Dialog Box (Also Known as UserForm) ....................................................................231 Creating Custom Dialog Boxes: An Overview...........................................232 Working with UserForms.............................................................................233 Inserting a new UserForm .................................................................233 Adding controls to a UserForm ........................................................234 Changing properties for a UserForm control..................................235 Viewing the UserForm Code window...............................................236 Displaying a custom dialog box........................................................237 Using information from a custom dialog box .................................237 A Custom Dialog Box Example ...................................................................238 Creating the custom dialog box........................................................238 Adding the CommandButtons ..........................................................238 Adding the OptionButtons ................................................................239 Adding event-handler procedures....................................................241 Creating a macro to display the dialog box ....................................243 Making the macro available ..............................................................243 Testing the macro...............................................................................244 Chapter 17: Using Dialog Box Controls . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .247 Getting Started with Dialog Box Controls .................................................247 Adding controls ..................................................................................247 Introducing control properties.........................................................248 Dialog Box Controls — the Details.............................................................250 CheckBox control ...............................................................................251 ComboBox control .............................................................................252 CommandButton control...................................................................253 Frame control......................................................................................253 Image control ......................................................................................254 Label control .......................................................................................254 ListBox control ...................................................................................255 MultiPage control ...............................................................................256 OptionButton control.........................................................................256 RefEdit control ....................................................................................257 ScrollBar control.................................................................................258 SpinButton control .............................................................................258

- 16. xiv Excel VBA Programming For Dummies TabStrip control..................................................................................259 TextBox control ..................................................................................259 ToggleButton control .........................................................................260 Working with Dialog Box Controls .............................................................260 Moving and resizing controls............................................................261 Aligning and spacing controls ..........................................................261 Accommodating keyboard users......................................................262 Testing a UserForm ............................................................................263 Dialog Box Aesthetics..................................................................................264 Chapter 18: UserForm Techniques and Tricks . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .265 Using Dialog Boxes.......................................................................................265 A UserForm Example ...................................................................................265 Creating the dialog box......................................................................266 Writing code to display the dialog box............................................268 Making the macro available ..............................................................268 Trying out your dialog box ...............................................................269 Adding event-handler procedures....................................................269 Validating the data..............................................................................271 Now the dialog box works.................................................................271 More UserForm Examples...........................................................................272 A ListBox example..............................................................................272 Selecting a range.................................................................................276 Using multiple sets of OptionButtons..............................................278 Using a SpinButton and a TextBox ...................................................278 Using a UserForm as a progress indicator ......................................280 Creating a tabbed dialog box ............................................................283 Displaying a chart in a dialog box ....................................................284 A Dialog Box Checklist.................................................................................286 Part V: Creating Custom Toolbars and Menus...............287 Chapter 19: Customizing the Excel Toolbars . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .289 Introducing CommandBars.........................................................................289 Customizing Toolbars..................................................................................289 Working with Toolbars ................................................................................291 The Toolbars tab ................................................................................292 The Commands tab ............................................................................294 The Options tab..................................................................................294 Adding and Removing Toolbar Controls...................................................295 Moving and copying controls ...........................................................295 Inserting a new control......................................................................295 Using other toolbar button operations ...........................................296 Distributing Toolbars...................................................................................297 Using VBA to Manipulate Toolbars............................................................298 Commanding the CommandBars collection ...................................299 Listing all CommandBar objects ......................................................299

- 17. Table of Contents xv Referring to CommandBars...............................................................300 Referring to controls in a CommandBar..........................................300 Properties of CommandBar controls ...............................................301 VBA Examples...............................................................................................302 Resetting all built-in toolbars............................................................302 Displaying a toolbar when a worksheet is activated .....................302 Ensuring that an attached toolbar is displayed .............................303 Hiding and restoring toolbars...........................................................304 Chapter 20: When the Normal Excel Menus Aren’t Good Enough . . .307 Defining Menu Lingo ....................................................................................307 How Excel Handles Menus ..........................................................................308 Customizing Menus Directly.......................................................................309 Looking Out for the CommandBar Object ................................................310 Referring to CommandBars...............................................................310 Referring to Controls in a CommandBar .........................................310 Properties of CommandBar Controls...............................................312 Placing your menu code ....................................................................313 Would You Like to See Our Menu Examples? ...........................................313 Creating a menu..................................................................................313 Adding a menu item ...........................................................................315 Deleting a menu ..................................................................................316 Deleting a menu item .........................................................................316 Changing menu captions ...................................................................317 Adding a menu item to the Tools menu...........................................318 Working with Shortcut Menus ....................................................................320 Adding menu items to a shortcut menu..........................................321 Deleting menu items from a shortcut menu ...................................321 Disabling shortcut menus .................................................................322 Finding Out More .........................................................................................322 Part VI: Putting It All Together ..................................323 Chapter 21: Creating Worksheet Functions — and Living to Tell about It . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .325 Why Create Custom Functions? .................................................................325 Understanding VBA Function Basics .........................................................326 Writing Functions .........................................................................................327 Working with Function Arguments ............................................................327 Function Examples.......................................................................................328 A function with no argument ............................................................328 A function with one argument ..........................................................328 A function with two arguments ........................................................330 A function with a range argument ....................................................331 A function with an optional argument .............................................332 A function with an indefinite number of arguments ......................334

- 18. xvi Excel VBA Programming For Dummies Using the Insert Function Dialog Box ........................................................335 Displaying the function’s description..............................................335 Function categories............................................................................336 Argument descriptions ......................................................................337 Chapter 22: Creating Excel Add-Ins . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .339 Okay . . . So What’s an Add-In? ...................................................................339 Why Create Add-Ins?....................................................................................340 Working with Add-Ins...................................................................................341 Add-in Basics ................................................................................................341 An Add-in Example.......................................................................................343 Setting up the workbook ...................................................................343 Testing the workbook ........................................................................346 Adding descriptive information .......................................................346 Creating the add-in .............................................................................347 Opening the add-in.............................................................................348 Distributing the add-in.......................................................................349 Modifying the add-in ..........................................................................349 Chapter 23: Interacting with Other Office Applications . . . . . . . . . . .351 Starting Another Application from Excel ..................................................351 Using the VBA Shell function ............................................................351 Activating a Microsoft Office application........................................352 Using Automation in Excel ..........................................................................352 Getting Word’s version number........................................................354 Controlling Word from Excel.............................................................355 Controlling Excel from Word.............................................................355 Sending Personalized E-mail Using Outlook .............................................358 Working with ADO........................................................................................360 Part VII: The Part of Tens...........................................363 Chapter 24: Ten VBA Questions (And Answers) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .365 The Top Ten Questions about VBA............................................................365 Chapter 25: (Almost) Ten Excel Resources . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .369 The VBA Help System ..................................................................................369 Microsoft Product Support .........................................................................369 Internet Newsgroups ...................................................................................370 Internet Web Sites ........................................................................................370 Excel Blogs ....................................................................................................371 Google............................................................................................................371 Local User Groups........................................................................................371 My Other Book .............................................................................................371 Index........................................................................373

- 19. Introduction G reetings, prospective Excel programmer . . . Thanks for buying my book. I think you’ll find that it offers a fast, enjoyable way to discover the ins and outs of Microsoft Excel programming. Even if you don’t have the foggiest idea of what programming is all about, this book can help you make Excel jump through hoops in no time (well, it will take some time). Unlike most programming books, this one is written in plain English, and even normal people can understand it. Even better, it’s filled with information of the “just the facts, ma’am” variety — and not the drivel you might need once every third lifetime. Is This the Right Book? Go to any large bookstore and you’ll find many Excel books (far too many, as far as I’m concerned). A quick overview can help you decide whether this book is really right for you. This book Is designed for intermediate to advanced Excel users who want to learn Visual Basic for Applications (VBA) programming. Requires no previous programming experience. Covers the most commonly used commands. Is appropriate for Excel 2000 through Excel 2003. Fact is, there are very few significant differences among Excel 2000, Excel 2002, and Excel 2003. Just might make you crack a smile occasionally — it even has cartoons.

- 20. 2 Excel VBA Programming For Dummies If you are using Excel 5, Excel 95, or Excel 97, this book is not for you. Although there are many similarities between the current version of Excel and previous versions, there are also many subtle (and not-so-subtle) differences that can be perplexing and can likely confuse you. If you’re still using a pre-2000 version of Excel, locate a book that is specific to that version. Or consider upgrading your copy of Excel. This is not an introductory Excel book. If you’re looking for a general-purpose Excel book, check out any of the following books, which are all published by Wiley: Excel 2003 For Dummies, by Greg Harvey Excel 2003 Bible, by John Walkenbach (yep, that’s me) Excel 2003 For Dummies Quick Reference, by John Walkenbach (me again) and Colin Banfield Notice that the title of this book isn’t The Complete Guide to Excel VBA Programming For Dummies. I don’t cover all aspects of Excel programming — but then again, you probably don’t want to know everything about this topic. In the unlikely event you want a more comprehensive Excel programming book, you might try Microsoft Excel 2003 Power Programming with VBA, by John Walkenbach (is this guy prolific, or what?), also published by Wiley Publishing. So You Want to Be a Programmer . . . Besides earning money to pay my bills, my main goal in writing this book is to teach Excel users how to use the VBA language — a tool that helps you sig- nificantly enhance the power of the world’s most popular spreadsheet. Using VBA, however, involves programming. (Yikes! The p word.) If you’re like most computer users, the word programmer conjures up an image of someone who looks and behaves nothing like you. Perhaps words such as nerd, geek, and dweeb come to mind. Times have changed. Computer programming has become much easier, and even so-called normal people now engage in this activity. Programming simply means developing instructions that the computer automatically carries out. Excel programming refers to the fact that you can instruct Excel to automati- cally do things that you normally do manually — saving you lots of time and (you hope) reducing errors. I could go on, but I need to save some good stuff for Chapter 1.

- 21. Introduction 3 If you’ve read this far, it’s a safe bet that you need to become an Excel pro- grammer. This could be something you came up with yourself or (more likely) something your boss decided. In this book, I tell you enough about Excel programming so that you won’t feel like an idiot the next time you’re trapped in a conference room with a group of Excel aficionados. And by the time you finish this book, you can honestly say, “Yeah, I do some Excel programming.” Why Bother? Most Excel users never bother to learn VBA programming. Your interest in this topic definitely places you among an elite group. Welcome to the fold! If you’re still not convinced that learning Excel programming is a good idea, I’ve come up with a few good reasons why you might want to take the time to learn VBA programming. It will make you more marketable. Like it or not, Microsoft’s applica- tions are extremely popular. You may already know that all applications in Microsoft Office support VBA. The more you know about VBA, the better your chances for advancement in your job. It lets you get the most out of your software investment (or, more likely, your employer’s software investment). Using Excel without knowing VBA is sort of like buying a TV set and watching only the odd-numbered channels. It will improve your productivity (eventually). Learning VBA definitely takes some time, but you’ll more than make up for this in the amount of time you ultimately save because you’re more productive. Sort of like what they told you about going to college. It’s fun (well, sometimes). Some people really enjoy making Excel do things that are otherwise impossible. By the time you finish this book, you just might be one of those people. Now are you convinced? What I Assume about You People who write books usually have a target reader in mind. For this book, my target reader is a conglomerate of dozens of Excel users I’ve met over the years (either in person or out in cyberspace). The following points more or less describe my hypothetical target reader:

- 22. 4 Excel VBA Programming For Dummies You have access to a PC at work — and probably at home. You’re running Excel 2000 or later. You’ve been using computers for several years. You use Excel frequently in your work, and you consider yourself to be more knowledgeable about Excel than the average bear. You need to make Excel do some things that you currently can’t make it do. You have little or no programming experience. You understand that the Help system in Excel can actually be useful. Face it, this book doesn’t cover everything. If you get on good speaking terms with the Help system, you’ll be able to fill in some of the missing pieces. You need to accomplish some work, and you have a low tolerance for thick, boring computer books. Obligatory Typographical Conventions Section All computer books have a section like this. (I think some federal law requires it.) Read it or skip it. Sometimes, I refer to key combinations — which means you hold down one key while you press another. For example, Ctrl+Z means you hold down the Ctrl key while you press Z. For menu commands, I use a distinctive character to separate menu items. For example, you use the following command to open a workbook file: File➪Open Excel programming involves developing code — that is, the instructions Excel follows. All code in this book appears in a monospace font, like this: Range(“A1:A12”).Select Some long lines of code don’t fit between the margins in this book. In such cases, I use the standard VBA line continuation character sequence: a space followed by an underscore character. Here’s an example: Selection.PasteSpecial Paste:=xlValues, _ Operation:=xlNone, SkipBlanks:=False, _ Transpose:=False

- 23. Introduction 5 When you enter this code, you can type it as written or place it on a single line (omitting the spaces and the underscore characters). Check Your Security Settings It’s a cruel world out there. It seems that some scam artist is always trying to take advantage of you or cause some type of problem. The world of com- puting is equally cruel. You probably know about computer viruses, which can cause some nasty things to happen to your system. But did you know that computer viruses can also reside in an Excel file? It’s true. In fact, it’s rel- atively easy to write a computer virus using VBA. An unknowing user can open an Excel file and spread the virus to other Excel workbooks. Over the years, Microsoft has become increasingly concerned about security issues. This is a good thing, but it also means that Excel users need to under- stand how things work. You can check Excel’s security settings by using the Tools ➪ Macro ➪ Security command. Your options are Very High, High, Medium, and Low. Check Excel’s Help system for details on these settings. Consider this scenario: You spend a week writing a killer VBA program that will revolutionize your company. You test it thoroughly, and then send it to your boss. He calls you into his office and claims that your macro doesn’t do anything at all. What’s going on? Chances are, your boss’s security setting does not allow macros to run. Or, maybe he chose to disable the macros when he opened the file. Bottom line? Just because an Excel workbook contains a macro it is no guar- antee that the macro will ever be executed. It all depends on the security set- ting and whether the user chooses to enable or disable macros for that file. In order to work with this book, you will need to enable macros for the files you work with. My advice is to use the Medium security level. Then, when you open a file that you’ve created, you can simply enable the macros. If you open a file from someone you don’t know, you should disable the macros and check the VBA code to ensure that it doesn’t contain anything destructive or malicious. How This Book Is Organized I divided this book into seven major parts, each of which contains several chapters. Although I arranged the chapters in a fairly logical sequence, you can read them in any order you choose. Here’s a quick preview of what’s in store for you.

- 24. 6 Excel VBA Programming For Dummies Part I: Introducing VBA Part I has but two chapters. I introduce the VBA language in the first chapter. In Chapter 2, I let you get your feet wet right away by taking you on a hands- on guided tour. Part II: How VBA Works with Excel In writing this book, I assumed that you already know how to use Excel. The four chapters in Part II give you a better grasp on how VBA is implemented in Excel. These chapters are all important, so I don’t recommend skipping past them, okay? Part III: Programming Concepts The eight chapters in Part III get you into the nitty-gritty of what program- ming is all about. You may not need to know all this stuff, but you’ll be glad it’s there if you ever do need it. Part IV: Developing Custom Dialog Boxes One of the coolest parts of programming in Excel is designing custom dialog boxes (well, at least I like it). The four chapters in Part IV show you how to create dialog boxes that look like they came straight from the software lab at Microsoft. Part V: Creating Custom Toolbars and Menus Part V has two chapters, both of which address user interface topics. One chapter deals with creating custom menus; the other describes how to cus- tomize toolbars. Part VI: Putting It All Together The four chapters in Part VI pull together information from the preceding chapters. You find out how to develop custom worksheet functions, create

- 25. Introduction 7 add-ins, design user-oriented applications, and even work with other Office applications. Part VII: The Part of Tens Traditionally, books in the For Dummies series contain a final part that con- sists of short chapters containing helpful or informative lists. Because I’m a sucker for tradition, this book has two such chapters that you can peruse at your convenience. (If you’re like most readers, you’ll turn to this part first.) Marginal Icons Somewhere along the line, a market research company must have shown that publishers can sell more copies of their computer books if they add icons to the margins of those books. Icons are those little pictures that supposedly draw your attention to various features, or help you decide whether some- thing is worth reading. I don’t know if this research is valid, but I’m not taking any chances. So here are the icons you’ll encounter in your travels from front cover to back cover: When you see this icon, the code being discussed is available on the Web. Download it, and eliminate lots of typing. See “Get the Sample Files,” below, for more information. This icon flags material you might consider technical. You might find it inter- esting, but you can safely skip it if you’re in a hurry. Don’t skip information marked with this icon. It identifies a shortcut that can save you lots of time (and maybe even allow you to leave the office at a rea- sonable hour). This icon tells you when you need to store information in the deep recesses of your brain for later use. Read anything marked with this icon. Otherwise, you may lose your data, blow up your computer, cause a nuclear meltdown — or maybe even ruin your whole day.

- 26. 8 Excel VBA Programming For Dummies Get the Sample Files This book has its very own Web site where you can download the example files discussed and view Bonus Chapters. To get these files, point your Web browser to: www.dummies.com/go/excelvba. Having the sample files will save you a lot of typing. Better yet, you can play around with them and experiment with various changes. In fact, I highly rec- ommend playing around with these files. Experimentation is the best way to learn VBA. Now What? Reading this introduction was your first step. Now, it’s time to move on and become a programmer (there’s that p word again!). If you’re a programming virgin, I strongly suggest that you start with Chapter 1 and progress in chapter order until you’ve discovered enough. Chapter 2 gives you some immediate hands-on experience, so you’ll have the illusion that you’re making quick progress. But it’s a free country (at least it was when I wrote these words); I won’t sic the Computer Book Police on you if you opt to thumb through randomly and read whatever strikes your fancy. I hope you have as much fun reading this book as I did writing it.

- 28. In this part . . . E very book must start somewhere. This one starts by introducing you to Visual Basic for Applications (and I’m sure you two will become very good friends over the course of a few dozen chapters). After the introductions are made, Chapter 2 walks you through a real-live Excel programming session.

- 29. Chapter 1 What Is VBA? In This Chapter Gaining a conceptual overview of VBA Finding out what you can do with VBA Discovering the advantages and disadvantages of using VBA Taking a mini-lesson on the history of Excel T his chapter is completely devoid of any hands-on training material. It does, however, contain some essential background information that assists you in becoming an Excel programmer. In other words, this chapter paves the way for everything else that follows and gives you a feel for how Excel programming fits into the overall scheme of the universe. Okay, So What Is VBA? VBA, which stands for Visual Basic for Applications, is a programming language developed by Microsoft — you know, the company run by the richest man in the world. Excel, along with the other members of Microsoft Office 2003, includes the VBA language (at no extra charge). In a nutshell, VBA is the tool that people like you and me use to develop programs that control Excel. Don’t confuse VBA with VB (which stands for Visual Basic). VB is a program- ming language that lets you create standalone executable programs (those EXE files). Although VBA and VB have a lot in common, they are different animals.

- 30. 12 Part I: Introducing VBA A few words about terminology Excel programming terminology can be a bit macro that adds color to some cells, prints the confusing. For example, VBA is a programming worksheet, and then removes the color, you language, but it also serves as a macro lan- have automated those three steps. guage. What do you call something written in By the way, macro does not stand for Messy VBA and executed in Excel? Is it a macro or is it And Confusing Repeated Operation. Rather, it a program? Excel’s Help system often refers to comes from the Greek makros, which means VBA procedures as macros, so I use that termi- large — which also describes your paycheck nology. But I also call this stuff a program. after you become an expert macro programmer. I use the term automate throughout this book. This term means that a series of steps is com- pleted automatically. For example, if you write a What Can You Do with VBA? You’re probably aware that people use Excel for thousands of different tasks. Here are just a few examples: Keeping lists of things such as customer names, students’ grades, or holiday gift ideas Budgeting and forecasting Analyzing scientific data Creating invoices and other forms Developing charts from data Yadda, yadda, yadda The list could go on and on, but I think you get the idea. My point is simply that Excel is used for a wide variety of things, and everyone reading this book has different needs and expectations regarding Excel. One thing virtually every reader has in common is the need to automate some aspect of Excel. That, dear reader, is what VBA is all about. For example, you might create a VBA program to format and print your month-end sales report. After developing and testing the program, you can execute the macro with a single command, causing Excel to automatically perform many time-consuming procedures. Rather than struggle through a tedious sequence of commands, you can grab a cup of joe and let your com- puter do the work — which is how it’s supposed to be, right?

- 31. Chapter 1: What Is VBA? 13 In the following sections, I briefly describe some common uses for VBA macros. One or two of these may push your button. Inserting a text string If you often need to enter your company name into worksheets, you can create a macro to do the typing for you. You can extend this concept as far as you like. For example, you might develop a macro that automatically types a list of all salespeople who work for your company. Automating a task you perform frequently Assume you’re a sales manager and need to prepare a month-end sales report to keep your boss happy. If the task is straightforward, you can develop a VBA program to do it for you. Your boss will be impressed by the consistently high quality of your reports, and you’ll be promoted to a new job for which you are highly unqualified. Automating repetitive operations If you need to perform the same action on, say, 12 different Excel workbooks, you can record a macro while you perform the task on the first workbook and then let the macro repeat your action on the other workbooks. The nice thing about this is that Excel never complains about being bored. Excel’s macro recorder is similar to recording sound on a tape recorder. But it doesn’t require a microphone. Creating a custom command Do you often issue the same sequence of Excel menu commands? If so, save yourself a few seconds by developing a macro that combines these commands into a single custom command, which you can execute with a single keystroke or button click. Creating a custom toolbar button You can customize the Excel toolbars with your own buttons that execute the macros you write. Office workers tend to be very impressed by this sort of thing.

- 32. 14 Part I: Introducing VBA Creating a custom menu command You can also customize Excel’s menus with your own commands that execute macros you write. Office workers are even more impressed by this. Creating a simplified front end In almost any office, you can find lots of people who don’t really understand how to use computers. (Sound familiar?) Using VBA, you can make it easy for these inexperienced users to perform some useful work. For example, you can set up a foolproof data-entry template so you don’t have to waste your time doing mundane work. Developing new worksheet functions Although Excel includes numerous built-in functions (such as SUM and AVERAGE), you can create custom worksheet functions that can greatly simplify your formulas. I guarantee you’ll be surprised by how easy this is. (I show you how to do this in Chapter 21.) Even better, the Insert Function dialog box displays your custom functions, making them appear built in. Very snazzy stuff. Creating complete, macro-driven applications If you’re willing to spend some time, you can use VBA to create large-scale applications complete with custom dialog boxes, onscreen help, and lots of other accoutrements. Creating custom add-ins for Excel You’re probably familiar with some of the add-ins that ship with Excel. For example, the Analysis ToolPak is a popular add-in. You can use VBA to develop your own special-purpose add-ins. I developed my Power Utility Pak add-in using only VBA.

- 33. Chapter 1: What Is VBA? 15 Advantages and Disadvantages of VBA In this section I briefly describe the good things about VBA — and I also explore its darker side. VBA advantages You can automate almost anything you do in Excel. To do so, you write instructions that Excel carries out. Automating a task by using VBA offers several advantages: Excel always executes the task in exactly the same way. (In most cases, consistency is a good thing.) Excel performs the task much faster than you could do it manually (unless, of course, you’re Clark Kent). If you’re a good macro programmer, Excel always performs the task without errors (which probably can’t be said about you or me). The task can be performed by someone who doesn’t know anything about Excel. You can do things in Excel that are otherwise impossible — which can make you a very popular person around the office. For long, time-consuming tasks, you don’t have to sit in front of your computer and get bored. Excel does the work, while you hang out at the water cooler. VBA disadvantages It’s only fair that I give equal time to listing the disadvantages (or potential disadvantages) of VBA: You have to learn how to write programs in VBA (but that’s why you bought this book, right?). Fortunately, it’s not as difficult as you might expect. Other people who need to use your VBA programs must have their own copies of Excel. It would be nice if you could press a button that trans- forms your Excel/VBA application into a stand-alone program, but that isn’t possible (and probably never will be).

- 34. 16 Part I: Introducing VBA A personal anecdote Excel programming has its own challenges and files. With a bit of sleuthing, I eventually discov- frustrations. One of my earlier books, Excel 5 ered that the readers who were having the For Windows Power Programming Techniques, problem had all upgraded to Excel 5.0c. (I devel- included a disk containing the examples from the oped my installation program using Excel 5.0a.) book. I compressed these files so that they would It turns out that the Excel 5.0c upgrade featured fit on a single disk. Trying to be clever, I wrote a a very subtle change that caused my macro to VBA program to expand the files and copy them bomb. Because I’m not privy to Microsoft’s to the appropriate directories. I spent a lot of time plans, I didn’t anticipate this problem. Needless writing and debugging the code, and I tested it to say, this author suffered lots of embarrass- thoroughly on three different computers. ment and had to e-mail corrections to hundreds of frustrated readers. Imagine my surprise when I started receiving e-mail from readers who could not install the Sometimes, things go wrong. In other words, you can’t blindly assume that your VBA program will always work correctly under all circumstances. Welcome to the world of debugging. VBA is a moving target. As you know, Microsoft is continually upgrading Excel. You may discover that VBA code you’ve written doesn’t work prop- erly with a future version of Excel. Take it from me; I discovered this the hard way, as detailed in the “A personal anecdote” sidebar. VBA in a Nutshell A quick and dirty summary follows of what VBA is all about. Of course, I describe all this stuff in semiexcruciating detail later in the book. You perform actions in VBA by writing (or recording) code in a VBA module. You view and edit VBA modules using the Visual Basic Editor (VBE). A VBA module consists of Sub procedures. A Sub procedure has noth- ing to do with underwater vessels or tasty sandwiches. Rather, it’s com- puter code that performs some action on or with objects (discussed in a moment). The following example shows a simple Sub procedure called Test. This amazing program displays the result of 1 plus 1. Sub Test() Sum = 1 + 1 MsgBox “The answer is “ & Sum End Sub

- 35. Chapter 1: What Is VBA? 17 A VBA module can also have Function procedures. A Function proce- dure returns a single value. You can call it from another VBA procedure or even use it as a function in a worksheet formula. An example of a Function procedure (named AddTwo) follows. This Function accepts two numbers (called arguments) and returns the sum of those values. Function AddTwo(arg1, arg2) AddTwo = arg1 + arg2 End Function VBA manipulates objects. Excel provides more than 100 objects that you can manipulate. Examples of objects include a workbook, a work- sheet, a cell range, a chart, and a shape. You have many, many more objects at your disposal, and you can manipulate them using VBA code. Objects are arranged in a hierarchy. Objects can act as containers for other objects. At the top of the object hierarchy is Excel. Excel itself is an object called Application, and it contains other objects such as Workbook objects and CommandBar objects. The Workbook object can contain other objects, such as Worksheet objects and Chart objects. A Worksheet object can contain objects such as Range objects and PivotTable objects. The term object model refers to the arrangement of these objects. (See Chapter 4 for details.) Objects of the same type form a collection. For example, the Work- sheets collection consists of all the worksheets in a particular work- book. The Charts collection consists of all Chart objects in a workbook. Collections are themselves objects. You refer to an object by specifying its position in the object hierar- chy, using a dot as a separator. For example, you can refer to the work- book Book1.xls as Application.Workbooks(“Book1.xls”) This refers to the workbook Book1.xls in the Workbooks collection. The Workbooks collection is contained in the Application object (that is, Excel). Extending this to another level, you can refer to Sheet1 in Book1.xls as Application.Workbooks(“Book1.xls”).Worksheets(“Sheet1”) As shown in the following example, you can take this to still another level and refer to a specific cell (in this case, cell A1): Application.Workbooks(“Book1.xls”).Worksheets(“Sheet1”).R ange(“A1”) If you omit specific references, Excel uses the active objects. If Book1. xls is the active workbook, you can simplify the preceding reference as follows: Worksheets(“Sheet1”).Range(“A1”)

- 36. 18 Part I: Introducing VBA If you know that Sheet1 is the active sheet, you can simplify the refer- ence even more: Range(“A1”) Objects have properties. You can think of a property as a setting for an object. For example, a Range object has such properties as Value and Address. A Chart object has such properties as HasTitle and Type. You can use VBA to determine object properties and to change properties. You refer to a property of an object by combining the object name with the property name, separated by a period. For example, you can refer to the value in cell A1 on Sheet1 as follows: Worksheets(“Sheet1”).Range(“A1”).Value You can assign values to variables. A variable is a named element that stores things. You can use variables in your VBA code to store such things as values, text, or property settings. To assign the value in cell A1 on Sheet1 to a variable called Interest, use the following VBA statement: Interest = Worksheets(“Sheet1”).Range(“A1”).Value Objects have methods. A method is an action Excel performs with an object. For example, one of the methods for a Range object is ClearContents. This method clears the contents of the range. You specify a method by combining the object with the method, separated by a dot. For example, the following statement clears the contents of cell A1: Worksheets(“Sheet1”).Range(“A1”).ClearContents VBA includes all the constructs of modern programming languages, including arrays and looping. Believe it or not, the preceding list pretty much describes VBA in a nutshell. Now you just have to find out the details. That’s the purpose of the rest of this book. An Excursion into Versions If you plan to develop VBA macros, you should have some understanding of Excel’s history. I know you weren’t expecting a history lesson, but this is important stuff. Here are all the major Excel for Windows versions that have seen the light of day, along with a few words about how they handle macros: