Perl Programming_Guide_Document_Refr.ppt

- 2. 2 What is Perl? • Practical Extraction and Report Language • A scripting language which is both relatively simple to learn and yet remarkably powerful.

- 3. 3 Introduction to Perl Perl is often described as a cross between shell programming and the C programming language. C (numbers) Shell programming (text) Smalltalk (objects) C++ (numbers, objects) Perl (text, numbers) Java (objects)

- 4. 4 Introduction to Perl • A “glue” language. Ideal for connecting things together, such as a GUI to a number cruncher, or a database to a web server. • Has replaced shell programming as the most popular programming language for text processing and Unix system administration. • Runs under all operating systems (including Windows). • Open source, many libraries available (e.g. database, internet) • Extremely popular for CGI and GUI programming.

- 5. 5 Why use Perl ? • It is easy to gain a basic understanding of the language and start writing useful programs quickly. • There are a number of shortcuts which make programming ‘easier’. • Perl is popular and widely used, especially for system administration and WWW programming.

- 6. 6 Why use Perl? • Perl is free and available on all computing platforms. – Unix/Linux, Windows, Macintosh, Palm OS • There are many freely available additions to Perl (‘Modules’). • Most importantly, Perl is designed to understand and manipulate text.

- 7. 7 Where to find help! • http://www.perl.com • http://www.perl.org

- 8. 8 Your first Perl script #!/usr/bin/perl #This script prints a friendly greeting to the screen print “Hello Worldn”; • Scripts are first “compiled” and then “executed” in the order in which the lines of code appear • You can write a script with any text editor. The only rule is that it must be saved as plain text.

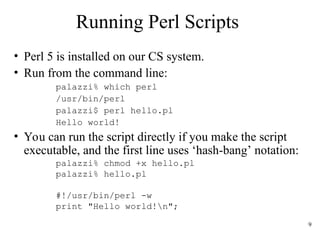

- 9. 9 Running Perl Scripts • Perl 5 is installed on our CS system. • Run from the command line: palazzi% which perl /usr/bin/perl palazzi$ perl hello.pl Hello world! • You can run the script directly if you make the script executable, and the first line uses ‘hash-bang’ notation: palazzi% chmod +x hello.pl palazzi% hello.pl #!/usr/bin/perl -w print "Hello world!n";

- 10. 10 Basic Syntax • The -w option tells Perl to produce extra warning messages about potential dangers. Always use this option- there is never (ok, rarely) a good reason not to. #!/usr/bin/perl -w • White space doesn't matter in Perl (like C++), except for #!/usr/bin/perl -w which must start from column 1 on line 1.

- 11. 11 Basic Syntax • All Perl statements end in a semicolon ; (like C) • In Perl, comments begin with # (like shell scripts) – everything after the # to the end of the line is ignored. – # need not be at the beginning of the line. – there are no C-like multi-line comments: /* */

- 12. 12 Perl Example • Back to our “Hello World” program: palazzi% hello.pl #!/usr/bin/perl -w # This is a simple Hello World! Program. print "Hello world!n"; –The print command sends the string to the screen, and “n“ adds a new line. –You can optionally add parentheses: print(Hello world!n);

- 13. 13 First Script Line by Line # This script prints a friendly greeting to the screen • This is a Perl ‘comment’. Anything you type after a pound sign (#) is not interpreted by the compiler. These are notes to yourself or a future reader. Comments start at the ‘#’ and end at a carriage return • #!/usr/bin/perl is NOT a comment (note this exception)

- 14. 14 First Script Line by Line print “Hello World!n”; • This is a Perl ‘statement’, or line of code • ‘print’ is a function - one of many • “Hello World!n” is a string of characters – note the ‘n’ is read as a single character meaning ‘newline’ • The semicolon ‘;’ tells the interpreter that this line of code is complete.

- 15. 15 Many ways to do it! 1. Welcome to Perl! 2. Welcome to Perl! 3. Welcome to Perl! 4. Welcome to Perl! 5. Welcome to Perl! 6. Welcome to Perl! # welcome.pl print ( "1. Welcome to Perl!n" ); print "2. Welcome to Perl!n" ; print "3. Welcome ", "to ", "Perl!n"; print "4. Welcome "; print "to Perl!n"; print "5. Welcome to Perl!n"; print "6. Welcomen tonn Perl!n";

- 16. 16 System Calls • You can use Perl to execute shell commands, just as if you were typing them on the command line. • Syntax: – `command` # note that ` is the ‘backtick’ character, not the single quote ‘

- 17. 17 A script which uses a system call • Note we are now using a ‘variable’ to hold the results of our system call #!/usr/bin/perl $directory_listing = `ls -l .`; print $directory_listing;

- 18. 18 Perl Variables and Truth

- 19. 19 What is a variable? • A named container for a single value – can be text or number – sometimes called a ‘scalar’ • A scalar variable has the following rules – Must start with a dollar sign ($) – Must not start with a number – Must not contain any spaces – May contain ‘a’ through ‘Z’, any number character, or the ‘_’ character

- 20. 20 Basic Types • Scalars, Lists and Hashes: – $cents=123; – @home=(“kitchen”, ”living room”, “bedroom”); – %days=( “Monday”=>”Mon”, “Tuesday”=>”Tues”); • All variable names are case sensitive.

- 21. 21 Scalars • Denoted by ‘$’. Examples: • $cents=2; • $pi=3.141; • $chicken=“road”; • $name=`whoami`; • $foo=$bar; • $msg=“My name is $name”; • In most cases, Perl determines the type (numeric vs. string) on its own, and will convert automatically, depending on context. (eg, printing vs. multiplying)

- 22. 23 Scalar variable names • These are valid names – $variable – $this_is_a_place_for_my_stuff – $Xvf34_B • These are invalid names – $2 – $another place for my stuff – $push-pull – $%percent

- 23. 24 Variable name tips • Use descriptive names – $sequence is much more informative than $x – $sequence1 is ok. $sequence_one is fine too • Avoid using names that look like functions – $print is probably bad (it will work!) • Try to avoid single letter variable names – $a and $b are used for something else – Experienced programmers will often use $i and $j as ‘counters’ for historical reasons.

- 24. 25 Operators Operator Description Example Result . String concatenate 'Teddy' . 'Bear' TeddyBear = Assignment $bear = 'Teddy' $bear variable contains 'Teddy' + Addition 3+2 5 - Subtraction 3-2 1 - Negation -2 -2 ! Not !2 0 * Multiplication 3*2 6 / Division 3/2 1.5 % Modulus 3%2 1 ** Exponentiation 3**2 9 . acts on strings only, ! on both strings and numbers, the rest on numbers only.

- 25. 26 A Perl calculator #!/usr/bin/perl $value_one = shift; #Takes the first argument from the command line $value_two = shift; #Takes the next argument from the command line $sum = $value_one + $value_two; $difference = $value_one - $value_two; $product = $value_one * $value_two; $ratio = $value_one / $value_two; $power = $value_one ** $value_two; print "The sum is: $sumn"; print "The difference is: $differencen"; print "The product is: $productn"; print "The ratio is: $ration"; print "The first number raised to the power of the second number is: $powern"; print ("I could have also written the sum as:", $value_one + $value_two, "n”);

- 26. 27 Quoting • When printing, use escapes (backslash) to print special characters: – print “She said ”Nortel cost $$cost @ $time”.” – Output: She said “Nortel cost $0.01 @ 10:00”. • Special chars: $,@,%,&,” • Use single quotes to avoid interpolation: – print ‘My email is [email protected]. Please send me $’; – (Now you need to escape single quotes.) • Another quoting mechanism: qq() and q() – print qq(She said “Nortel cost $$cost @ $time”.); – print q(My email is [email protected]. Please send me $); – Useful for strings full of quotes.

- 27. 28 Backquotes: Command Substitution • You can use command substitution in Perl like in shell scripts: $ whoami bhecker #!/usr/bin/perl -w $user = `whoami`; chomp($user); $num = `who | wc -l`; chomp($num); print "Hi $user! There are $num users logged on.n"; $ test.pl Hi bhecker! There are 6 users logged on. • Command substitution will usually include a new line, so use chomp().

- 28. 29 Backquote Example #!/usr/local/bin/perl -w $dir = `pwd`; chomp($dir); $big = `ls -l | sort +4 | tail -1 | cut -c55-70`; chomp($big); $nline = `wc -l $big | cut -c6-8`; # NOTE: Backquotes # interpolate. chomp($nline); $nword = `wc -w $big | cut -c6-8 `; chomp($nword); $nchar = `wc -c $big | cut -c6-8 `; chomp($nchar); print "The biggest file in $dir is $big.n"; print "$big has $nline lines, $nword words, $nchar characters.n"; $ big1 The biggest file in /homes/horner/111/perl is big1. big1 has 14 lines, 66 words, 381 characters.

- 29. 30 Quotes and more Quotes - Recap • There is a fine distinction between double quoted strings and single quoted strings: – print “$variablen” # prints the contents of $variable and then a newline – print ‘$variablen’ # prints the string $variablen to the screen • Single quotes treat all characters as literal (no characters are special) • You can always specify a character to be treated literally in a double quoted string: – print “I really want to print a $ charactern”;

- 30. 31 Even more options • the qq operator – print qq[She said “Hi there, $stranger”.n] ; #same as – print “She said ”Hi there, $stranger”.n” ; • qq means change the character used to denote the string – Almost any non-letter character can be used, best to pick one not in your string • print qq$I can print this stringn$; • print qq^Or I can print this stringn^; • print qq &Or this onen&; – perl thinks that if you use a ‘(‘, ‘[‘, or ‘{‘ to open the string, you mean to use a ‘)’, ‘]’, or ‘}’ to close it

- 31. 32 What is Truth? • A question debated by man since before cave art. • A very defined thing in PERL. – Something is FALSE if: • a) it evaluates to zero • b) it evaluates to ‘’ (empty string) • c) it evaluates to an empty list (@array = “”) • d) the value is undefined (ie. uninitialized variable) – Everything else is TRUE

- 32. 33 Numeric Comparison Operators Operator Description Example Result == Equality 2 == 2 TRUE != Non Equality 2 !=2 FALSE > Greater Than 3>2 TRUE < Less Than 3<2 FALSE <= Greater Than or Equal 3<=2 TRUE >= Less Than or Equal 3>=2 FALSE <=> Comparison 3 <=> 2 1 " 2 <=> 3 -1 " 3 <=> 3 0 • Do not confuse ‘=‘ with ‘==‘ !!!! •<=> is really only useful when using the ‘sort’ function

- 33. 34 String (Text) Comparison Operators •cmp is really only useful when using the ‘sort’ function Operator Description Example Result eq Equality 'cat' eq 'cat' TRUE ne Non Equality 'cat' ne 'cat' FALSE gt Greater Than 'data' gt 'cat' TRUE lt Less Than 'data' lt 'cat' FALSE ge Greater Than or Equal 'data' ge 'cat' TRUE le Less Than or Equal 'data' le 'cat' FALSE cmp Comparison 'data' cmp 'cat' 1 " 'cat' cmp 'data' -1 " 'cat' cmp 'cat' 0

- 34. 35 What did you mean? • To make your life ‘easier’, Perl has only one data type for both strings (characters) and numbers. • When you use something in numeric context, Perl treats it like a number. – $y = ‘2.0’ + ‘1’; # $y contains ‘3’ – $y = ‘cat’ + 1; # $y contains ‘1’ • When you use something in string context, perl treats it like a string. – $y = ‘2.0’ . ‘1’; # $y contains ‘2.01’ • In short, be careful what you ask for!!

- 35. 36 More Truth • Statements can also be TRUE or FALSE, and this is generally logical – a) 1 == 2 - false – b) 1 !=2 - true – c) ‘dog’ eq ‘cat’ - false – d) (1+56) <= (2 * 100) – true – e) (1-1) – false! - evaluates to zero – f) ‘0.0’ - true! Tricky. – g) ‘0.0’ + 0 - false! Even trickier.

- 36. 37 Functions • Functions are little bundles of Perl code with names. They exist to make it easy to do routine operations • Most functions do what you think they do, to find out how they work type: – perldoc -f function_name

- 37. 38 A Perl Idiom - if • if is a function which does something if a condition is true. – print “Number is 2” if ($number == 2); • Of course, there is also a function that does the opposite - unless – print “Number isn’t 2” unless ($number == 2); • You don’t ever need to use unless, unless you want to... – print “Number isn’t 2” if ($number != 2);

- 38. 39 More about if • A frequent Perl construction is the if/elsif/else construct – if (something){ do something } – elsif (something else) { do something } – else { do the default thing } • The block of code associated with the first true condition is executed. • Note: elsif, not elseif

- 39. 40 Traditional usage of if #!/usr/bin/perl # bigger.pl $value = shift; unless ($value =~ /^d+$/ ){ print “$value contains a non-digit character. Integers are all digits!n”; die; } if ($value > 100){ print “$value is bigger than 100n”; } elsif ($value1 >= 10){ print “$value is 10 or greater n”; } else { print “$value is smaller than 10n” }

- 40. 41 Control flow if ($foo==10) { print “foo is tenn”; } print “foo is ten” if ($foo==10); if ($today eq “Tuesday”) { print “Class at four.n”; } elsif ($today eq “Friday”) { print “See you at the bar.n”; } else { print “What’s on TV?n”; }

- 41. 42 Control flow You’ve already seen a while loop. for loops are just like C: for ($i=0; $i<10; $i++) { print “i is $In”; }

- 42. 43 Getting at your data (Input and Output)

- 43. 44 A brief Diversion • Get into the habit of using the -w flag – mnemonic (Warn me when weird) • Enables more strict error checking – Will warn you when you try to compare strings numerically, for example. • Usage – command line: ‘perl -w script.pl’ • even more diversion: ‘perl -c script.pl’ compiles but does not run script.pl – Or line: #!/usr/bin/perl -w

- 44. 45 Concepts to know Input Data Any program Output Data STDIN STDERR STDOUT

- 45. 46 Data flow • Unless you say otherwise: – Data comes in through STDIN (Standard IN) – Data goes out through STDOUT (Standard Out) – Errors go to STDERR (Standard Error) • Error code contained in a ‘magic’ variable $!

- 46. 47 User Input • Use <STDIN> to get input from the user: #!/usr/bin/perl -w print "Enter name: "; $name = <STDIN>; chomp ($name); print "How many pens do you have? "; $number = <STDIN>; chomp($number); print "$name has $number pen!n"; $ test.pl Enter name: Barbara Hecker How many pens do you have? one Barbara Hecker has one pen.

- 47. 48 User Input • <STDIN> grabs one line of input, including the new line character. So, after: $name = <STDIN>; if the user typed “Barbara Hecker[ENTER]”, $name will contain: “Barbara Heckern”. • To delete the new line, the chomp() function takes a scalar variable, and removes the trailing new line if present. • A shortcut to do both operations in one line is: chomp($name = <STDIN>);

- 48. 49 Numerical Example #!/usr/bin/perl -w print "Enter height of rectangle: "; $height = <STDIN>; print "Enter width of rectangle: "; $width = <STDIN>; $area = $height * $width; print "The area of the rectangle is $arean"; $ test.pl Enter height of rectangle: 10 Enter width of rectangle: 5 The area of the rectangle is 50 $ test.pl Enter height of rectangle: 10.1 Enter width of rectangle: 5.1 The area of the rectangle is 51.51

- 49. 50 An idiom - while • while a condition is true, do a block of statements • If you really want to know... The opposite of while is until • The most common use of while is for reading and acting on lines of data from a file

- 50. 51 #while_count.pl while ($val < 5){ print “$valn”; $val++; } Usage of while • while the condition is true ($val is less than 5), do something (print $val) • ‘++’? Same at C/C++

- 51. 52 Shortcut operators • Sometimes called auto operators (auto-increment, auto-decrement) • Optimized for speed and efficiency Operator Usage Read as: ++ $i++ $i = $i + 1 -- $i-- $i = $i - 1 += $i += 20 $i = $i + 20 -= $i -= 5 $i = $i - 5 *= $i *= 2 $i = $i * 2 /= $i /= 2 $i = $i / 2 .= $i .= 'foo' $i = $i . 'foo'

- 52. 53 #line_count.pl while ($val = <>){ $line++; print “$line:t$valn”; } Reading (and modifying) a file • Perl Magic! <> – Opens the file (or files) given as arguments on the command line – Brings in one line of data at a time

- 53. 54 Filehandles • A filehandle is a way to interact with input or output – ‘<>’ interacts with files on the command line • filehandle names are simple strings with no symbols – I usually use all caps (SEQFILE), but that isn’t necessary • You must open your filehandle before using it

- 54. 55 Opening Filehandles • Open a file for reading – open NAME, “<filename”; • This is default behavior, so you don’t actually need the ‘<‘ • Open file for writing – open NAME, “>filename”; #open new file • Warning: If filename already exists, it is overwritten!! – open NAME, “>>filename”; # append to old file

- 55. 56 Filehandle • Flexible coding – I want to specify the file to open on the command line, rather than hard coding it $in_name = shift; $out_name = shift; open FILE, “<$in_name” or die “Couldn’t open $in_name for reading: $!n”; open OUT, “>$out_name” || die“Couldn’t open $out_name for reading: $!n”; while ($line = <FILE>){ chomp $line; print OUT “Something about $linen } • Usage: <$> myscript.pl inputfile outputfile

- 56. 57 When do I use a filehandle? • You can get away with not using them, mostly. – STDIN is fine (<>) and you can always capture your STDOUT to a file with a redirect (>) on the command line. – <$> myscript.pl file_in > file_out • If you are using two input files for different purposes or want more than one output file, you need filehandles – <> will slurp all the input files on command line! – > on the command line will put all output to one file

- 57. 58 Perl as Duct Tape (the force that glues the universe together) • The STDOUT of one script can serve as the STDIN of another script. – use the pipe (‘|’) symbol to chain scripts together • Nothing goes to the screen in between scripts – instead, what would normally go to the screen is redirected and made the STDIN of the next script

- 58. 59 Lists and More Lists (Perl Arrays)

- 59. 60 A brief diversion • strict – forces you to ‘declare’ a variable the first time you use it. – usage: use strict; (somewhere near the top of your script) • declare variables with ‘my’ – usage: my $variable; – or: my $variable = ‘value’; • my sets the ‘scope’ of the variable. Variable exists only within the current block of code • use strict and my both help you to debug errors, and help prevent mistakes.

- 60. 61 What is an array? • A named container for a list of values – can be text or number, or mix – An array is an ordered list. • Array names follow the same rules as scalar variables – No spaces – a-Z 0-9 and ‘_’ only – Cannot start with a number

- 61. 62 Making an array • @my_array = (1,15,’cat’, 23, ‘blue’); – Note this is a comma separated list, enclosed in parentheses. The parentheses are very important!! • A tricky way: – @my_array = qw (1 15 cat blue); • mnemonic: qw - ‘Quote Words’ • Remember no commas if you use qw!

- 62. 63 A picture might help • @my_array = (1,15,’cat’, 23, ‘blue’); • @my_array 0 1 2 3 4 1 15 ‘cat’ 23 ‘blue’ Element # Contents

- 63. 64 Getting at the Array Elements • @my_array = (5, ‘boo’, ‘16’, ‘hoo’); • $my_array[1] contains ‘boo’ – Pay attention! The way this is written is important • An array element is a single (scalar) value • Starts with the $ sign (just like a scalar) not the @ sign • Square braces indicate the array position (index, or element number) • Perl counts from zero!! First element is $my_array[0]

- 64. 65 Manipulating Array Elements • You can do anything to an array element that you can do to a scalar. – $my_array[2] = ‘scary’; • Of course you can do an assignment (=) • list now is (5, ‘boo’, ‘scary’, ‘hoo’) – $string = $my_array[2].$my_array[1] • $string contains ‘scaryboo’ – $my_array[5] = ‘16’; • list now (5, ‘boo’, ‘scary’, ‘hoo’, ‘’, ’16’) • your list is as long as it needs to be!

- 65. 66 A Common Mistake • @array is not the same as $array – One is an array, one is a scalar. – To get at an array element, must use square braces. ($array[$i]) – The square braces are how Perl knows you are talking about an array – You may have both @array and $array at the same time. They are completely different, and not related in any way at all. • Since they are different, use different names and don’t confuse yourself.

- 66. 67 Some useful tricks • copy an array – @array_copy = @array; • join two arrays – @array_join = (@array1,@array2); • reverse the order of an array – @array_flip = reverse(@array); • print an array (simple method) – print @array; # prints elements with no spaces – print “@array”; # prints elements separated by single space

- 67. 68 Some more useful tricks • Getting at the last element – $last_element = $my_array[-1]; • negative indices count backwards • Counting the number of elements – $count = scalar @array; • If we use a list in a scalar context, we get the number of elements in the list. Same as: – $count = @array; • In other words, if we try to use an array (list) in the same way as a single (scalar) variable, perl makes our array into a number.

- 68. 69 List or Scalar Context • Some functions behave differently if given a list than if given a scalar. • An example: – @array2 = reverse @array1; • now @array2 contains the elements in @array1 in reversed order - we’ve seen this already • list context - reverse is given a list as an argument – $reversedword = reverse $word; • if $word contained ‘Hello’, $reversedword contains ‘olleH’ • scalar context - reverse is given a scalar as an argument

- 69. 70 Visiting each item in a list • foreach element (list){do something interesting} #!/usr/bin/perl -w use strict; my @list = ('pkc','pkd', 'mapk32', 'efgr'); my $count = 1; my $item; foreach $item (@list){ print "Element number $count is $itemn"; $count++ }

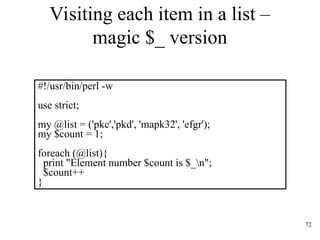

- 70. 71 Some Tricky Bits (a magic variable) • The default scalar variable - $_ • In a looping structure (foreach and while, for example), if you don’t specify a loop variable, the value will be assigned to $_ instead. • In general, any function which acts on a scalar (chomp and print, for example) will act on $_ unless told otherwise. • It is easier to show it than to describe it...

- 71. 72 Visiting each item in a list – magic $_ version #!/usr/bin/perl -w use strict; my @list = ('pkc','pkd', 'mapk32', 'efgr'); my $count = 1; foreach (@list){ print "Element number $count is $_n"; $count++ }

- 72. 73 Making an array from a file #!/usr/bin/perl -w use strict; my @array; while (my $line = <>){ chomp $line; @array = (@array,$line); # push (@array, $line); # a way we don’t know yet } now do something cute with @array •Assuming each line of your file is to be a single element in your array...

- 74. 75 pop and push • Sometimes, you want to do something with the end of a list. – pop : removes the last element from a list – $last_value = pop @array #or pop (@array) – push : adds an element to the end of a list – push @array, $value # or push (@array,’value’) • Both push and pop change the array. • Remember, push onto the end, pop off the end.

- 75. 76 shift and unshift • Sometimes, you want to do something to the front of a list – shift : takes the first element off of the list – $value = shift @array # or $value = shift(@array) – unshift : puts an element at the front of the list – unshift @array, $value # or unshift (@array,$value) • shift and unshift also change the array • Remember: shift off of the front, unshift onto the front

- 76. 77 Haven’t I seen shift before? • You may recall that we used shift to get arguments into our script in the second class: – my $value1 = shift; #get command line argument • This is another example of perl using a default variable. • Since we didn’t specify an array, it assumed we meant @ARGV (the invocation argument array) – same as typing : my $value = shift @ARGV;

- 77. 78 Split! • split is a very useful function – Takes a string and splits it into an array – You choose what character (or characters) to split on • split (/pattern/, string) – where pattern is what to split on and string is what to split – the split function returns a list

- 78. 79 Using Split • my @array = split (/s/,$string); or my @array = split (“s”, $string); or my @array = split “s”; or my @array = split; • Examples: – split (/s/, ‘a few words’); • returns a list containing (‘a’, ‘few’, ‘words’) – split (/x/, ‘ABxCXxDDxxEFGx’); • returns (‘AB’, ‘CX’, ‘DD’, ‘’, ‘EFG’) • Note that the character you split on is ‘destroyed’ - it doesn’t appear in your list

- 79. 80 Join: The anti-split • join : takes an array as its argument, and returns a string. • join (glue, list); • example: $string = join (‘glue’, @array); – if array contained (‘foo’, 15, ‘bar’)... – $string = ‘fooglue15gluebar’ • Whatever the ‘glue’ is will the the string in between the array elements. – You can (and often want to) use ‘’ as the glue

- 80. 81 Example: Removing embedded new lines from a file #!/usr/bin/perl -w use strict; $/ = ">"; #change the ‘record separator’ from n to the ‘>’ character <>; # get the first record (just a ‘>’). No assignment, so it disappears! while ($record = <>){ chomp $record; my ($name,@seqs) = split ("n”, $record); my $sequence = join (‘’, @seqs); print ">$namen$sequencen"; }

- 81. 82 Sorting an Array • You frequently wish to sort a list. • Two kinds of sorting: – Alphabetical (the default in perl) – Numeric • sort always takes a list as its argument, and returns a list – @sorted = sort(@array) • The argument to sort can be something that returns a list. So, you could do: – @sort_split = sort (split (“t”,$line));

- 82. 83 Sorting an Array (continued) • Default sort is actually: – @sorted = sort {$a cmp $b} @list; • If ‘cmp’ looks familiar, it should. Remember: – ‘cmp’ : string comparison operator – ‘<=>’ : numeric comparison operator • Both return 1, 0, or -1 • It logically follows that if we want to sort a list numerically: – @sorted_num = sort {$a <=> $b} @list;

- 83. 84 More sorting • $a and $b cannot be renamed. sort is funny that way. Learn the magic incantation! • How might you sort in reverse order? – @sort_reverse = sort {$b cmp $a}@list; – swapping the order of $a and $b changes the sort order • You can make the sort block as complicated as you want. – @sort_abs = sort { abs($a) <=> abs($b) }@num; – this sorts on the absolute value of a list of numbers

- 85. 86 What is a regular expression? • A regular expression (regex) is simply a way of describing text. • Regular expressions are built up of small units which can represent the type and number of characters in the text • Regular expressions can be very broad (describing everything), or very narrow (describing only one pattern).

- 86. 87 Why would you use a regex? • Often you wish to test a string for the presence of a specific character, word, or phrase – Examples • “Are there any letter characters in my string?” • “Is this a valid accession number?”

- 87. 88 Constructing a Regex • Pattern starts and ends with a / /pattern/ – if you want to match a /, you need to escape it • / (backslash, forward slash) – you can change the delimiter to some other character, but you probably won’t need to • m|pattern| • any ‘modifiers’ to the pattern go after the last / • i : case insensitive /[a-z]/i • o : compile once • g : match in list context (global) • m or s : match over multiple lines

- 88. 89 Looking for a pattern • By default, a regular expression is applied to $_ (the default variable) – if (/a+/) {die} • looks for one or more ‘a’ in $_ • If you want to look for the pattern in any other variable, you must use the bind operator – if ($value =~ /a+/) {die} • looks for one or more ‘a’ in $value • The bind operator is in no way similar to the ‘=‘ sign!! = is assignment, =~ is bind. – if ($value = /[a-z]/) {die} • Looks for one or more ‘a’ in $_, not $value!!!

- 89. 90 Regular Expression Atoms • An ‘atom’ is the smallest unit of a regular expression. • Character atoms • 0-9, a-Z match themselves • . (dot) matches everything • [atgcATGC] : A character class (group) • [a-z] : another character class, a through z

- 90. 91 More atoms • d - All Digits • D - Any non-Digit • s - Any Whitespace (s, t, n) • S - Any non-Whitespace • w - Any Word character [a-zA-Z_0-9] • W - Any non-Word character

- 91. 92 An example • if your pattern is /ddd-dddd/ – You could match • 555-1212 • 5512-12222 • 555-5155-55 – But not: • 55-1212 • 555-121 • 555j-5555

- 92. 93 Quantifiers • You can specify the number of times you want to see an atom. Examples • d* : Zero or more times • d+ : One or more times • d{3} : Exactly three times • d{4,7} : At least four, and not more than seven • d{3,} : Three or more times • We could rewrite /ddd-dddd/ as: – /d{3}-d{4}/

- 93. 94 Anchors • Anchors force a pattern match to a certain location • ^ : start matching at beginning of string • $ : start matching at end of string • b : match at word boundary (between w and W) • Example: • /^ddd-dddd$/ : matches only valid phone numbers

- 94. 95 Grouping • You can group atoms together with parentheses • /cat+/ matches cat, catt, cattt • /(cat)+/ matches cat, catcat, catcatcat • Use as many sets of parentheses as you need

- 95. 96 Alternation • You can specify patterns which match either one thing or another. – /cat|dog/ matches either ‘cat’ or ‘dog’ – /ca(t|d)og/ matches either ‘catog’ or ‘cadog’

- 96. 97 Precedence • Just like with mathematical operations, regular expressions have an order of precedence – Highest : Parentheses and grouping – Next : Repetition (+,*, {4}) – Next : Sequence (/abc/) – Lowest : Alternation ( | )

- 97. 98 Examples of precedence • If we represent sequence with a ‘. ’ – in other words : /abc/ becomes /a. b. c/ • /a. b*. c/ matches abc, abbc, ac, etc. • /a. b. c*/ matches ab, abcc, abccc, etc. • /(a. b. c)+/ matches abc, abcabc, etc. • /c. a. t|d. o. g/ matches cat or dog • /(c. a. t)|(d. o. g)/ matches cat or dog • /c. a. (t|d). o. g/ matches catog or cadog

- 98. 99 Variable interpolation • You can put variables into your pattern. – if $string = ‘cat’ • /$string/ matches ‘cat’ • /$string+/ matches ‘cat’, ‘catcat’, etc. • /d{2}$string+/ matches ‘12cat’, ‘24catcat’, etc.

- 99. 100 Remembering Stuff • Being able to match patterns is good, but limited. • We want to be able to keep portions of the regular expression for later. – Example: $string = ‘phone: 353-7236’ • We want to keep the phone number only • Just figuring out that the string contains a phone number is insufficient, we need to keep the number as well.

- 100. 101 Memory Parentheses (pattern memory) • Since we almost always want to keep portions of the string we have matched, there is a mechanism built into perl. • Anything in parentheses within the regular expression is kept in memory. – ‘phone:353-7236’ =~ /^phone:(.+)$/; • Perl knows we want to keep everything that matches ‘.+’ in the above pattern

- 101. 102 Getting at pattern memory • Perl stores the matches in a series of default variables. The first parentheses set goes into $1, second into $2, etc. – This is why we can’t name variables ${digit} – Memory variables are created only in the amounts needed. If you have three sets of parentheses, you have ($1,$2,$3). – Memory variables are created for each matched set of parentheses. If you have one set contained within another set, you get two variables (inner set gets lowest number) – Memory variables are only valid in the current scope

- 102. 103 An example of pattern memory my $string = shift; if ($string =~ /^phone:(d{3}-d{4})$/){ $phone_number = $1; } else { print “Enter a phone number!n” }

- 103. 104 Some tricky bits • You can assign pattern memory directly to your own variable names: – ($phone) = $value =~ /^phone:(.+)$/; • Read from right to left. Bind (apply) this pattern to the value in $value, and assign the results to the list on the left – ($front,$back) = /^phone:(d{3})-(d{4})/; • Bind this pattern to $_ (!!!) and assign the results to the list on the left

- 104. 105 List or scalar context? • A pattern match returns 1 or 0 (true or false) in a scalar context, and a list of matches in array context. • There are a lot of functions that do different things depending on whether they are used in scalar or list context. • $count = @array # returns the number of elements • $revString = reverse $string # returns a reversed string • @revArray = reverse @array # returns a reversed list

- 105. 106 Practical Example of Context • $phone = $string =~ /^.+:(.+)$/; – $phone contains 1 if pattern matches, 0 if not – scalar context!!! – This is why this worked! unless (/^d+$/){ die} • ($phone) = $string =~ /^.+:(.+)$/; – $phone contains the matched string – list context!!!

- 106. 107 Finding all instances of a match • Use the ‘g’ modifier to the regular expression – @sites = $sequence =~ /(TATTA)/g; – think g for global – Returns a list of all the matches (in order), and stores them in the array – If you have more than one pair of parentheses, your array gets values in sets • ($1,$2,$3,$1,$2,$3...)

- 107. 108 Perl is Greedy • In addition to taking all your time, perl regular expressions also try to match the largest possible string which fits your pattern – /ga+t/ matches gat, gaat, gaaat – ‘Doh! No doughnuts left!’ =~ /(d.+t)/ • $1 contains ‘doughnuts left’ • If this is not what you wanted to do, use the ‘?’ modifier – /(d.+t)/ # match as few ‘.’s as you can and still make the pattern work

- 108. 109 Making parenthesis forgetful • Sometimes you need parenthesis to make your regex work, but you don’t actually want to keep the results. You can still use parentheses for grouping. • /(?:group)/ – yet another instance of character reuse. • d? means 0 or 1 instances • d+? means the fewest non zero number of digits (don’t be greedy) • (?:group) means look for the group of atoms in the string, but don’t remember it.

- 109. 110 Substitute function • s/pattern1/pattern2/; • Looks kind of like a regular expression – Patterns constructed the same way • Inherited from previous languages, so it can be a bit different. – Changes the variable it is bound to!

- 110. 111 Using s • Substituting one word for another – $string =~ s/dogs/cats/; • If $string was “I love dogs”, it is now “I love cats” • Removing trailing white space – $string =~ s/s+$//; • If $string was ‘ATG ‘, it is now ‘ATG’ • Adding 10 to every number in a string – $string =~ /(d+)/$1+10/ge; • If string was “I bought 5 dogs at 2 bucks each”, it is now: – “I bought 15 dogs at 12 bucks each” • Note pattern memory!! • g means global (just like a regex) • e is special to s, evaluate the expression on the right

- 111. 112 tr function • translate or transliterate • tr/characterlist1/characterlist2/; • Even less like a regular expression than s • substitutes characters in the first list with characters in the second list $string =~ tr/a/A/; # changes every ‘a’ to an ‘A’ – No need for the g modifier when using tr.

- 112. 113 Using tr • Creating complimentary DNA sequence – $sequence =~ tr/atgc/TACG/; • Sneaky Perl trick for the day – tr does two things. • 1. changes characters in the bound variable • 2. Counts the number of times it does this – Super-fast character counter™ • $a_count = $sequence =~ tr/a/a/; • replaces an ‘a’ with an ‘a’ (no net change), and assigns the result (number of substitutions) to $a_count

- 113. 114 Intro to Modules and Build your own (web) Robot

- 114. 115 • A module is basically a collection of subroutines (and sometimes variables) that increases the abilities of Perl • Often, modules are put together by other people, and distributed for public use • Two types of modules: – Standard (built in): Modules which are so useful (or popular) that they are included with the standard distributions of Perl – Custom installed : Modules which are added to a distribution of perl by an end user What is a Module?

- 115. 116 • The File::Basename module (imports functions) #!/usr/bin/perl use strict; use File::Basename; my $path = ‘/disk2/gcg/users/seqs.fsa’; my $file = basename($path); my $dir = dirname($path); print “The file name is $file in the directory $dirn”; Using a module (example)

- 116. 117 • The Env module (imports variables) #!/usr/bin/perl –w use strict; use Env; print “My home is $HOMEn”; print “My path is $PATHn”; print “My username is $USERn”; Using another Module

- 117. 118 Using A Module • Modules are as different as the people who write them. • A good module will have good documentation, with examples • perldoc ModuleName will get you the documentation • You may see object oriented syntax with arrows – $record = new->($param);

- 118. 119 Where do I get modules? • Many modules are already installed with your distribution of Perl • If you are in doubt, try to look at the documentation, if a module is installed you will be able to read the docs. • All public modules are available through CPAN (Comprehensive Perl Archive Network) www.CPAN.org

- 119. 120 Getting data from the web • Problem: Everybody posts data on the web, nobody knows how to get it off easily. • Problem: Cutting and pasting from web pages is unsatisfying, and hard on the hands and wrists • Problem: You want the most up to date information from a web resource • Answer: Create a Perl script which acts as your agent on the web (a ‘Robot’)

- 120. 121 Before you become a Robot... • As with all power, this power can be used for good, or for evil • If you plan on getting a lot of data, consider the possibility that there may be another (easier to use) source of the data • It is considered rude to request very large amounts of data, or to request at a frequency which denies the resource to other users • This technology can be used to mount DOS (denial of service) attacks. Don’t do this, even by accident • The website administrator may, without your permission, cut you off in self defense. Or cut off your entire university. Don’t be the idiot who ruins it for everybody.

- 121. 122 Baby Steps: Beginning Robotics • Unfortunately, you need to know a little about how HTML is written and deciphered. This is learned through practice and by looking at examples • Almost everything you will want to do in a scripting languages can be accomplished by using a simple Perl module. • There are more powerful and (potentially deceptive) things that can be done with all sorts of Perl modules.

- 122. 123 The ‘Static’ URL Request • Some resources are ‘static’ pages, which present the same data on each request (http://www.csuhayward.edu). • Each web page has an address (URL – Uniform Resource Locator), which uniquely identifies it on the internet • Static pages are easy to collect data from, since they don’t change from request to request

- 123. 124 Constructing the Robot • Now that we know the URL, we can mimic human interaction with the web resource using Perl • We do four relatively simple things – 1. Construct a text string which looks like a valid request – 2. Use LWP::Simple to submit this text string as a web request – 3. Retrieve the web page as a single text string (record) – 4. Get the information we desire out of the record.

- 124. 125 Using Modules • Some handy modules: – FileHandle (more intuitive filehandle library) – LWP::Simple (simple web ops – page fetching, etc). – XML::RSS (an RSS/RDF parser). – Date::Tolkien::Shire (do date manipulation in the Shire calendar.) – Thousands more..

- 125. 126 What is LWP::Simple • It is a set of Perl modules which provides a simple and consistent application programming interface (API) to the World- Wide Web. The main focus of the library is to provide classes and functions that allow you to write WWW clients. • The library also contain modules that are of more general use and even classes that help you implement simple HTTP servers.

- 126. 127 Constructing the Robot (example) #!/usr/bin/perl –w use strict; use LWP::Simple; # tell Perl we want LWP::Simple functions # Create a string which looks like a valid URL my $URL_string = ‘http://www.csuhayward.edu/”; # Use the LWP::Simple ‘get’ function to request the page my $results = get($URL_string); print $results;

- 127. 128 The ‘dynamic’ URL Request • Some online resources present different content, based on user input. They are ‘dynamic’, in the sense that they change their output based on a response to user input. • Most of these online resources interact with the end user through CGI (Common Gateway Interface) scripts, which are often written in Perl. • Regardless of the scripting language, CGI scripts get user input through parameters, and these parameters are passed through the URL request. • You have to know what this request looks like, in order to properly pose as a human user.

- 128. 129 The Request (Decoded) • Often, you can see what your request looks like right in your browser. • http://www.ncbi.gov/UniGene/clust.cgi?ORG=Mm&CID=7 • Everything up to the ‘?’ character is the URL • In this case, ‘clust.cgi’ is the name of the script which processes the web request • Everything after the ‘?’ are parameters passed to the script – Parameter ‘ORG’ = Mm – Parameter ‘CID’ = 7

- 129. 130 Constructing the ‘Dynamic’ Robot • Now that we know the URL and the parameters it is expecting, we can mimic human interaction with the web resource using Perl • We do the same four relatively simple things – 1. Construct a text string which looks like a valid request – 2. Use LWP::Simple to submit this text string as a web request – 3. Retrieve the web page as a single text string (record) – 4. Get the information we desire out of the record.

- 130. 131 Phase 1: Construct the request string • 1. Decide which parameters are going to change, and make them into variables. my $URL_front = ‘http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/UniGene/clust.cgi? ORG=Mm&CID=’; my $cluster = shift; chomp $cluster; my $request = $URL_front.$cluster;

- 131. 132 Phase 2 and 3: Make the request and save the results use LWP::Simple; # LWP::Simple is part of the standard Perl installation my $record = get($request); # get is the function from LWP::Simple that does the work

- 132. 133 Phase 4: Interpreting the results • In order to get rid of all of the extra junk, you need to ‘parse’ your results. • Parsing is a fancy word for a process which involves: – 1. Understanding the structure of the string (where are all of the relevant parts?) – 2. Constructing some way to uniquely identify the parts you want (regular expressions are good...) – 3. Yanking out the parts you want and returning them in some useful format.

- 133. 134 Get and Post • There are two basic methods for passing parameters over the web. • Get : puts the parameters into the URL, you can see them in your browser address bar • Post : hides the parameter list from your address bar • Obviously a ‘get’ request is easier for you, the novice roboteer, to interpret and act on

- 134. 135 Figuring out Post parameters • Post requests are harder. Unfortunately, there is no really easy way to figure them out • Look at the source for the page • In particular, look for a section that says something like <form action=‘scriptname’> • In this section are all the parameters that a particular script accepts, and probably some other neat information

- 135. 136 End of Lecture

![31

Even more options

• the qq operator

– print qq[She said “Hi there, $stranger”.n] ; #same as

– print “She said ”Hi there, $stranger”.n” ;

• qq means change the character used to denote the

string

– Almost any non-letter character can be used, best to pick

one not in your string

• print qq$I can print this stringn$;

• print qq^Or I can print this stringn^;

• print qq &Or this onen&;

– perl thinks that if you use a ‘(‘, ‘[‘, or ‘{‘ to open the

string, you mean to use a ‘)’, ‘]’, or ‘}’ to close it](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/perlprogrammingguide-250128124019-9100a54e/85/Perl-Programming_Guide_Document_Refr-ppt-30-320.jpg)

![48

User Input

• <STDIN> grabs one line of input, including the new

line character. So, after:

$name = <STDIN>;

if the user typed “Barbara Hecker[ENTER]”, $name

will contain: “Barbara Heckern”.

• To delete the new line, the chomp() function takes a

scalar variable, and removes the trailing new line if

present.

• A shortcut to do both operations in one line is:

chomp($name = <STDIN>);](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/perlprogrammingguide-250128124019-9100a54e/85/Perl-Programming_Guide_Document_Refr-ppt-47-320.jpg)

![64

Getting at the Array Elements

• @my_array = (5, ‘boo’, ‘16’, ‘hoo’);

• $my_array[1] contains ‘boo’

– Pay attention! The way this is written is important

• An array element is a single (scalar) value

• Starts with the $ sign (just like a scalar) not the @ sign

• Square braces indicate the array position (index, or

element number)

• Perl counts from zero!! First element is $my_array[0]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/perlprogrammingguide-250128124019-9100a54e/85/Perl-Programming_Guide_Document_Refr-ppt-63-320.jpg)

![65

Manipulating Array Elements

• You can do anything to an array element

that you can do to a scalar.

– $my_array[2] = ‘scary’;

• Of course you can do an assignment (=)

• list now is (5, ‘boo’, ‘scary’, ‘hoo’)

– $string = $my_array[2].$my_array[1]

• $string contains ‘scaryboo’

– $my_array[5] = ‘16’;

• list now (5, ‘boo’, ‘scary’, ‘hoo’, ‘’, ’16’)

• your list is as long as it needs to be!](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/perlprogrammingguide-250128124019-9100a54e/85/Perl-Programming_Guide_Document_Refr-ppt-64-320.jpg)

![66

A Common Mistake

• @array is not the same as $array

– One is an array, one is a scalar.

– To get at an array element, must use square braces.

($array[$i])

– The square braces are how Perl knows you are talking

about an array

– You may have both @array and $array at the same

time. They are completely different, and not related

in any way at all.

• Since they are different, use different names and

don’t confuse yourself.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/perlprogrammingguide-250128124019-9100a54e/85/Perl-Programming_Guide_Document_Refr-ppt-65-320.jpg)

![68

Some more useful tricks

• Getting at the last element

– $last_element = $my_array[-1];

• negative indices count backwards

• Counting the number of elements

– $count = scalar @array;

• If we use a list in a scalar context, we get the

number of elements in the list. Same as:

– $count = @array;

• In other words, if we try to use an array (list) in the

same way as a single (scalar) variable, perl makes

our array into a number.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/perlprogrammingguide-250128124019-9100a54e/85/Perl-Programming_Guide_Document_Refr-ppt-67-320.jpg)

![88

Constructing a Regex

• Pattern starts and ends with a / /pattern/

– if you want to match a /, you need to escape it

• / (backslash, forward slash)

– you can change the delimiter to some other character, but you

probably won’t need to

• m|pattern|

• any ‘modifiers’ to the pattern go after the last /

• i : case insensitive /[a-z]/i

• o : compile once

• g : match in list context (global)

• m or s : match over multiple lines](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/perlprogrammingguide-250128124019-9100a54e/85/Perl-Programming_Guide_Document_Refr-ppt-87-320.jpg)

![89

Looking for a pattern

• By default, a regular expression is applied to $_ (the default

variable)

– if (/a+/) {die}

• looks for one or more ‘a’ in $_

• If you want to look for the pattern in any other variable, you must

use the bind operator

– if ($value =~ /a+/) {die}

• looks for one or more ‘a’ in $value

• The bind operator is in no way similar to the ‘=‘ sign!! = is

assignment, =~ is bind.

– if ($value = /[a-z]/) {die}

• Looks for one or more ‘a’ in $_, not $value!!!](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/perlprogrammingguide-250128124019-9100a54e/85/Perl-Programming_Guide_Document_Refr-ppt-88-320.jpg)

![90

Regular Expression Atoms

• An ‘atom’ is the smallest unit of a regular

expression.

• Character atoms

• 0-9, a-Z match themselves

• . (dot) matches everything

• [atgcATGC] : A character class (group)

• [a-z] : another character class, a through z](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/perlprogrammingguide-250128124019-9100a54e/85/Perl-Programming_Guide_Document_Refr-ppt-89-320.jpg)

![91

More atoms

• d - All Digits

• D - Any non-Digit

• s - Any Whitespace (s, t, n)

• S - Any non-Whitespace

• w - Any Word character [a-zA-Z_0-9]

• W - Any non-Word character](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/perlprogrammingguide-250128124019-9100a54e/85/Perl-Programming_Guide_Document_Refr-ppt-90-320.jpg)