Workshop Final Report - Training-Workshop to Develop Concept Notes of Indigenous Peoples for the Green Climate Fund for Community-Based Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation

- 1. LAND AND WATER Applying RAPTA to Indigenous People’s Green Climate Fund Concept Notes UNDP, Bangkok, 7-8 February 2017

- 2. ii Citation Butler,J.R.A. 2017. ApplyingRAPTA toIndigenousPeople’sGreenClimateFundConceptNotes.Workshop Reportto the UnitedNationsDevelopmentProgram,7-8February2017. CSIROLand and Water,Brisbane 40 pp. Contact details CSIROLand and Water,GPO Box 2583, Brisbane,QLD 4001, Australia [email protected] Cover photo Workshopparticipantpresenting keyissues forthe Kenyacase study (UNDP) Copyright and disclaimer © 2015 CSIROTo the extentpermittedbylaw,all rightsare reservedandnopart of thispublication coveredbycopyrightmaybe reproducedorcopiedinanyform or byany meansexceptwiththe written permissionof CSIRO. Important disclaimer CSIROadvisesthat the informationcontainedinthispublicationcomprisesgeneral statementsbasedon scientificresearch.The readerisadvisedandneedstobe aware thatsuch informationmaybe incomplete or unable tobe usedinanyspecificsituation.Noreliance oractionsmusttherefore be made onthat informationwithoutseekingpriorexpertprofessional,scientificandtechnical advice.Tothe extent permittedbylaw,CSIRO(includingitsemployeesandconsultants) excludesall liabilitytoanypersonfor any consequences,includingbutnotlimitedtoall losses,damages,costs,expensesandanyother compensation,arisingdirectlyorindirectlyfromusingthispublication(inpartorinwhole) andany informationormaterial containedinit.

- 3. 3 Contents Executive summary..................................................................................................................................4 1 Background.................................................................................................................................7 1.1 The Resilience, Adaptation Pathways and Transformation Assessment (RAPTA) framework ...7 1.2 IndigenousPeople’s Green Climate Fund concept notes.......................................................8 1.3 Case studies ......................................................................................................................9 1.4 RAPTA components..........................................................................................................10 2 Workshop sessions....................................................................................................................11 2.1 System Description..........................................................................................................11 2.2 System Assessment..........................................................................................................11 2.3 Options and Pathways......................................................................................................12 3 Vietnam case study ...................................................................................................................13 3.1 System Description..........................................................................................................13 3.2 System Assessment..........................................................................................................14 3.3 Options and Pathways......................................................................................................16 4 Nepal case study.......................................................................................................................18 4.1 System Description..........................................................................................................18 4.2 System Assessment..........................................................................................................19 4.3 Options and Pathways......................................................................................................22 5 Nicaragua case study.................................................................................................................25 5.1 System Description..........................................................................................................25 5.2 System Assessment..........................................................................................................27 5.3 Options and Pathways......................................................................................................27 6 Kenya case study.......................................................................................................................31 6.1 System Description..........................................................................................................31 6.2 System Assessment..........................................................................................................33 6.3 Options and Pathways......................................................................................................33 7 Conclusions andevaluation........................................................................................................37 7.1 Applying RAPTA to GCF ....................................................................................................37 7.2 Evaluation.......................................................................................................................38 8 References................................................................................................................................40

- 4. 4 Executive summary The Resilience,AdaptationPathwaysandTransformationAssessmentframework(RAPTA) began developmentbyCSIROin2016 followingarequestbythe Scientificand Technical AdvisoryPanel of the Global EnvironmentFacility.RAPTA seekstoapplyexistingprinciplesof resilience,transformation, adaptationpathwaysandlearningtothe scoping,designandimplementationof large development programs.While manyof these conceptsare well-established, todate theyhave notbeenappliedwithina single framework,oras a cohesive ‘toolbox’,tointentionallyintervenein complexsystemsandachieve sustainabilitygoals.RAPTA is now beingtestedandrefinedbyCSIROanditspartnersthrough various developmentprogramplanningactivities. In thiscase,CSIROwas invitedbythe UnitedNationsDevelopmentProgram’s(UNDP) Climate Change AdaptationUnit,Bangkok,toassistinthe designof conceptnotesby IndigenousPeople’srepresentatives for submissiontothe GreenClimate Fund(GCF).On the 7th and part of 8th February2017, JamesButler fromCSIRO Land andWater demonstratedtoolsfrom the SystemDescription,SystemAssessmentand OptionsandPathwayscomponentsof RAPTA usingfourcase studiesfromVietnam, Nepal,Nicaraguaand Kenya.Usingcausal loopanalysis,Theoryof Change andinterventionpathways,20Indigenous representatives, three UNDP andfive consultancy participantsanalysedpriority climateand development challengesandidentifiedkeyinterventionsinthe case studysystems,andthe sequencingof actionsto achieve transformational change.Althoughtooshortandlimitedtoallow a full multi-stakeholderRAPTA processfor eachcase study,the 1 ½ dayexercise servedtohighlightpriorityinterventionsthatcouldform GCF projectproposals.Foreachcase study,these were: Vietnam(Tay,Nung,Hmong San,Diu,Dzao, San Chi,Caolan,Hoaand Kinh ethnicgroups,Thai NguyenProvince):The priority issuewasunstable uplandagriculturalproductivity causeddirectly by increasedclimate variabilityandreducedwater flows fromnative forests.The priority interventionwasthe allocationof publicforestlandstolocal ethnicgroupstobe managedunder successful traditional practices throughco-managementwithgovernment. Nepal (Gorung,Tamang,Magar and Dura ethnicgroupsin the Lamjungregion): The priority issue was uplandwaterscarcity,causeddirectlybylongerdryseasons,inappropriateforestrypolicies, and the introductionof non-native vegetation.The priorityinterventionwasthe strengtheningof traditional natural resource managementandknowledge. Nicaragua (MiskituethnicgroupfromHaulover,IndigenousTerritoryof PrinzuAwalUn):The priority issue wascoastal erosion,causedbysandextraction,weakcustomarypoliciesand institutions,deforestation, lackof awarenessof climate change,andintensifiedwavesandflooding. The priorityinterventionwasstrengthenednatural resource managementnorms. Kenya (Maasai ethnicgroupfrom Narok and Kajiado Counties):The priority issue wasfamine, causeddirectlybydrought,cross-borderrestrictionsonmovement,limitedlivelihoodoptions, constrainedaccesstowater andpoor pasture management.The priorityinterventionwasthe restorationandstrengtheningof cultural normsandpracticesforrangelandmanagement. Participantsthendeveloped aTheoryof Change forthe implementationof theirinterventions.Following thisexercise, projectactivitieswere sequencedtominimise risksposedbyfuture uncertainty.The resulting ‘implementationpathways’formedthe basisforpotential GCFprojectplans.

- 5. 5 A causal loop diagram being prepared by the Kenya case study group, which focussed on famine (UNDP) A comparison between the priorityRAPTA interventions identifiedbythe fourcase studies andthe initial GCF conceptnotes’objectives developedpriortothe workshopshowedsome changes(TableA). For VietnamandNepal the focus remained similar,withthe managementof publicforestsandstrengthening traditional forestmanagement,respectively.ForNicaragua the emphasisalteredfromterritorial governance tostrengtheningcoastal natural resource management,andinKenyaasimilarshiftwas evidentforpastoralism. The RAPTA interventionswere more specificthanthe GCFobjectives becausethey targetedunderlying directand indirectcausesof climate anddevelopmentproblems,theircomplex linkages andrelated‘viciouscycles’.Asa result,theywere potentially transformational, eventhoughthey didnot necessarilyaddressclimate issuesdirectly.The RAPTA analysisnow providesthe case studies’ representativeswithaclearerrationale andjustificationfortheirGCFconceptnotes,anda potentially transformational setof targetedinterventions.The draftimplementationpathwaysalsoprovide alogical planfor future programactivities whichaccountforfuture uncertainty. Table A. Draft GCF conceptnote objectives developedforthe fourcase studies priortothe RAPTA workshop,andthe priorityinterventionidentified asaresultof the RAPTA exercise. Case study Pre-workshop concept note Priority RAPTA intervention Vietnam Community ownership and co-management of Allocation of public forestlands to local ethnic forests between government and communities groups to be managed under proven to sequester carbon and promote adaptation traditional practices through co-management with government Nepal Awareness raisingon resilienceto climate Strengthening traditional natural resource change; capacity-buildingof Indigenous people management and knowledge and their traditional knowledgeand practices; alternativelivelihood development; information dissemination Nicaragua Strengthen territorial governanceand Strengthen coastal natural resource livelihoods to adaptto climatechange management norms Kenya Enhance resilienceof pastoralistlivelihoods; Restoration and strengthening of cultural facilitatean enablingenvironment for norms and practices of rangeland pastoralism;enhance knowledge generation management

- 6. 6 At the endof the workshop eachparticipantwasaskedtowrite a single statementaboutthe primary learningtheyhadderivedfromthe RAPTA exercise.A range of answerswere given,andthe followingare examples: “It is very important to know the vicious circle of problems, direct/indirect causes to address both indirect/direct impacts and end up with activities to implement and right interventions” “Need to prioritise the activities, but we also need to consider the uncertainty of futures and possible risk – especially for infrastructure or activity with higher risk. Need to have enough information, consultation, meetings to minimise risk and optimise higher impact to meet the goal” “My analytical and critical skills have deeply been enhanced and strengthened” “I learned a systems assessment and the feedback loops which determines what priority interventions to take” “RAPTA is like mathematics – with a formula,systemicway of doing things (system assessment) and a way of checking (feedbackloops).Theequation getscompleted when you areable to point outwhereyou should begin your intervention” “I can work in a different context, even if I don’t have expertise in one area/issue” “I think in a different way” “RAPTA could be easy to use with communities – flexible methodology” “Prioritise interventions/sequence activities with keeping in mind uncertainty and changes in conditions” “Very good training with logical framework – I will apply it in project design – I will use the tool to train others, especially local communities” “It really fits into the GCF standardsin the sense that they were looking how the project affects the people”

- 7. 7 1 Background 1.1 The Resilience, Adaptation Pathways and Transformation Assessment (RAPTA) framework The worldis changingat an unprecedentedrate.Through globalization,local communitiesandthe social- ecological systemsthattheyare partof are becomingmore complex,inter-connected, dynamicand unpredictable.Thisrequiresanewapproachto the designandimplementationof development projects. Insteadof assumingsimple cause-and-effectrelationships,projectdesignmustunderstandthe complex systemsthattheyare interveningin,andallow foruncertaintiesintheiroperatingenvironment. Withresponse to thischallenge,in2016 the ScientificandTechnical AdvisoryPanel of the Global EnvironmentFacility invitedCSIROtodevelopthe Resilience,AdaptationPathwaysandTransformation Assessmentframework(RAPTA).RAPTA seekstoapplyexistingprinciplesof systems,resilience, transformation,adaptationpathwaysandlearningtothe scoping,designandimplementationof large developmentprograms (O’Connelletal.2016). While manyof these conceptsare well-established,they have not beenappliedwithinasingle framework,orasa cohesive ‘toolbox’,tointentionallyintervene in complex systems toachieve sustainabilitygoals.RAPTA consistsof sevencomponents (Figure 1): 1. Scoping:A standard componentof projectdevelopmentthatsummarisesthe purpose andnature of the project,andmightinvolve a‘lightpass’of RAPTA. 2. Engagementand Governance:Stakeholderengagementseekstodevelopsharedunderstandingof the many perspectivesof problemsandsolutions. Thiscomponentdefinesthe roles, responsibilitiesandaccountabilitiesof stakeholdersinvolvedinprojectdesign, implementationand governance. 3. Theory of Change:A Theoryof Change isa keyactivity whichoutlinesthe assumedlinkages betweenprojectgoals,impacts,outcomes,outputsand activities.ItunderpinsMonitoringand Assessment(M&A) andprojectevaluation. 4. SystemDescription:Drawingfromstakeholders’diverseperspectives,thiscomponentproducesan understandingof the featuresandcharacteristicsof the systemconcerned. 5. SystemAssessment:Thiscomponentidentifieskeydynamicsandfeedbackloopsinthe system, its potential alternativestates, andopportunitiesforadaptationortransformation. 6. Optionsand Pathways:The interventionoptionsare identifiedandarrangedintoaprovisional orderfor implementation whichallowsforfuture uncertainty.Thisformsanimplementationplan whichcan be activelyupdatedandadaptively managedovertime throughthe Learning component. 7. Learning:Thiscomponentencompasses M&A andconnectsall othercomponents.Resultsof M&A informadaptive managementand ongoingtestingof the Theory of Change.The engagementof stakeholders inLearningisessential toenhance self-assessment,awarenessof theirrolesand their capacityto influence futureaction. Followingthis orderisnotessential:usersshouldchoose asequence thatbestsuitstheirproject.Each projectis itself acomplex system,andrequires aflexibility tolearnandadaptin a sequence that best

- 8. 8 servesitsgoals. Equally,differenttoolscanbe appliedfromthe toolboxtosuitthe contextandtime available.The keyisthatstakeholdersare engagedtotake a systemsview of the problemstheyare aiming to tackle,withinanadaptive learningapproach. Figure 1. The RAPTA frameworkandcomponents,inputs,outcomesandpotential meta-indicatorstoassess a RAPTA process’seffectiveness(fromO’Connell etal.2016). 1.2 Indigenous People’s Green Climate Fund concept notes RAPTA isbeingtestedandrefinedbyCSIROanditspartnersthroughvariousdevelopmentprogram planningactivities.Inthiscase,CSIROwasinvitedbythe UnitedNationsDevelopmentProgram’s(UNDP) Climate Change AdaptationUnit,Bangkok,toassistinthe designof conceptnotesbyIndigenousPeople’s representativesforsubmissiontothe GreenClimate Fund(GCF). Onthe 7th and part of 8th February2017, JamesButlerfromCSIROLand and Water joinedaplanningworkshopwhichincluded20representativesof Indigenous organisations,three UNDPandfive consultancyparticipants. On6th February,the Indigenous representatives hadbegundesigningtheirpreliminaryGCFconceptnotes,andpresentedthesefor discussiontothe UNDP. RAPTA meta-indicators • Summary action indicators • Coverage • Quality of process • Learning priorities • Impact of interventions • On-ground outcomes RAPTA FRAMEWORK Outputs and outcomes Will include • Project planning documents • Options and pathways, learning frameworks to take to next phase of project cycle • Identified key knowledge gaps • Improved capacity of stakeholders to understand system and manage adaptively Inputs May include • Data, models, evidence from range of sources • Existing indicators reported to Conventions, GEF, national processes, or from literature May need to develop new indicators or models or collect new data to fill identified knowledge gaps

- 9. 9 Nine Indigenous organisationswere represented,fromAsia,AfricaandSouthAmerica: CenterforResearchand DevelopmentinUplandAreas(CERDA),Vietnam CenterforIndigenousPeoplesResearchandDevelopment(CIPRED),Nepal IndigenousPeoples’International Centre forPolicyResearchandEducation (Tebtebba),Philippines InstitutDayakologi,Indonesia IndigenousLivelihoodEnhancementPartners(ILEPA),Kenya Lelewal Foundation,Cameroon CenterforIndigenousPeoples'Autonomy andDevelopment(CADPI),Nicaragua Federationforthe Self-determinationof IndigenousPeoples, Paraguay CenterforIndigenousPeoples'Cultures,Peru Participants in the Indigenous People’s Green Climate Fund workshop (UNDP) 1.3 Case studies To illustrate RAPTA toolsandprocesses,itwasdecidedtofocusonfour case studies.These were partly determinedbythe presence of participantswhohadanin-depthknowledge of the regionsconcerned.The case studieswere: Vietnam: The Tay,Nung,Hmong San,Diu,Dzao, SanChi,Caolan,Hoa and Kinhethnicgroupsfrom Thai NguyenProvince Nepal: Gorung,Tamang,Magar and Dura ethnicgroupsinthe LamjungRegion Nicaragua:MiskituethnicgroupfromHaulover,IndigenousTerritoryof PrinzuAwal Un Kenya:Maasai ethnicgroupfromNarokand KajiadoCounties

- 10. 10 1.4 RAPTA components Due to the limitedtimeavailable(1½ days),andinorder to informthe developmentof the GCFconcept notes,itwas decidedtofocusonthree RAPTA components:SystemDescription, SystemAssessment,and OptionsandPathways.The SystemsDescriptionwouldencourage participantstoconceptualise the case studiesassystems.The SystemAssessmentwasdesignedtofocusonthe key linkagesamongstthe systems,andinterventionpoints thatcouldachieve transformational change.Thiswouldassistparticipants to prioritise and justifyinterventionsinthese termsintheirGCFproposals.Finally,the Optionsand Pathwayswouldencourage participantsto designthe implementationof theirproposalsinthe contextof future uncertaintyandrapidchange.While notcomprehensive,the participatoryexerciseswereintended to illustrate some of the toolsappliedinRAPTA,buildthe capacityof the participantstouse these intheir ownwork,and supportthe developmentof the GCF proposalsbyCERDA (Vietnam), CIPRED(Nepal), CADPI (Nicaragua) andILEPA (Kenya).

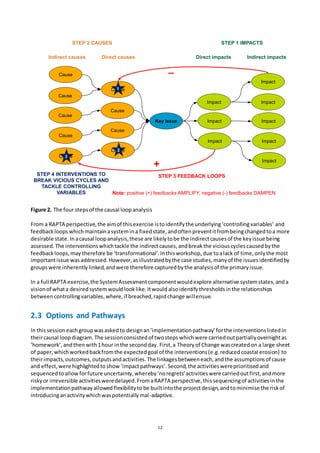

- 11. 11 2 Workshop sessions 2.1 System Description Priorto startingthe workshopprocess,the participantswere dividedintofourgroups,one foreachcase study.Membersof CERDA (Vietnam), CIPRED(Nepal),CADPI (Nicaragua)andILEPA (Kenya) ledeach group’sdiscussion,since theyhadfirst-handknowledgeof the case studies. These groupswerejoinedby Indigenousrepresentativesfromthe same region(e.g. the IndigenousPeoples’International Centrefor PolicyResearchandEducation,Philippines,tookpartinthe Vietnamcase study).The UNDPstaff alsojoined the groups,and contributedtheirgeneralknowledge of climate change anddevelopmentissues,rather than specificinformationoneachcase study.Inthisway,each groupintentionallycombinedlocal,regional and external orexpertknowledge andperspectives,whichisanimportantprinciple forconductingRAPTA. The SystemDescription session wasallocated1hour.Each group wasaskedto describe the following aspectsof theircase study: The location and geography The local ethnicgroupsconcerned The historyof itspeople andenvironment Relevantcultural andpoliticaldynamics,andinfluencesfromoutside orwithinthe location The keyissuesanddriversaffectingdevelopmentinthe location The intentionwastoencourage participantstoconsiderthe characteristicsand dynamicsof theircase study,andpresentthisas a story.In thiscase, the tool we applied wasbasedon ParticipatorySystemic Inquiry,whichisdefinedas“learninganddeliberationwhichinvolvesmultiplestakeholdersingenerating deepinsightsinto the dynamicsof the systemsthattheyare tryingtochange” (Burns2012, p. 88). The ‘system’concernedisthe webof causal relationshipsbetweenissuesthatstakeholders are concerned about,and embeddedwithin. Byconsideringissues(e.g. poverty),dynamics(e.g. historical eventswhich have determinedcurrentissues), andcross-scale linkages(e.g. national government policiesdrivinglocal outcomes),participantsbegantotake asystemsview of theircase study. 2.2 System Assessment The secondsession, SystemAssessment,wasallocatedatotal of 4 hours,anddividedintotwoparts.The firstpart was allocated1hour, whengroupsdiscussedandlistedthe key developmentissuesineachcase study,andthenrankedthemin termsof importance.The aimof thisprocesswasto identifythe major driversorbarriersto developmentwithinthe system concerned. The secondpart was allocated3 hours,andinvolvedgroupsconductinga‘causal loopanalysis’forthe highest-rankedissueintheircase study ona large piece of flipchartpaper.A causal loopanalysis breaks downa problemfroma systemsperspective,inorderto expose the causal linkagesandpinpoint key intervention pointsneededtochange the system.Inthiscase,the tool wasone modified byButleretal. (2015) fromCIFOR andSEI (2009). The firststep requiresparticipantstoconsiderthe ‘downstream’ direct and indirectimpactsof the issue andtheirlinkages.Thisisfollowedbyaninvestigationof the ‘upstream’ directand indirectcauses,andtheirlinkages.Next,possible feedbackloopsbetweenimpactsandcauses are considered.Theseare differentiatedaspositive,whichamplifythe effectsof impactsoncauses, and negative,whichdampenthese effects. Inthe final step,interventionsare designedtointerveneinthe ‘viciouscycles’createdbythe feedbackloops,whichexacerbateandmaintainthe issue concerned(Figure 2). These interventionsare alsoranked byimportance.

- 12. 12 Figure 2. The four stepsof the causal loopanalysis From a RAPTA perspective,the aimof thisexercise istoidentifythe underlying‘controllingvariables’ and feedbackloops whichmaintainasystemina fixedstate,andoftenpreventitfrombeingchangedtoa more desirable state.In acausal loopanalysis,these are likelytobe the indirectcausesof the keyissue being assessed.The interventionswhichtackle the indirectcauses, andbreakthe viciouscyclescausedbythe feedbackloops,may therefore be ‘transformational’. Inthisworkshop,due toalack of time,onlythe most importantissue wasaddressed.However,asillustratedbythe case studies,manyof the issuesidentifiedby groups were inherentlylinked,andwere therefore capturedby the analysisof the primaryissue. In a full RAPTA exercise,the SystemAssessmentcomponentwouldexplore alternative systemstates,anda visionof whata desiredsystemwouldlooklike. Itwould alsoidentify thresholds inthe relationships betweencontrollingvariables,where,if breached,rapidchange willensue. 2.3 Options and Pathways In thissession eachgroupwasaskedto designan‘implementationpathway’forthe interventionslistedin theircausal loopdiagram. The sessionconsistedof twosteps whichwere carriedoutpartiallyovernightas ‘homework’,andthenwith1hour inthe secondday.First,a Theoryof Change wascreatedon a large sheet of paper,whichworkedbackfromthe expectedgoal of the interventions(e.g.reducedcoastal erosion) to theirimpacts,outcomes,outputsandactivities.The linkagesbetweeneach,andthe assumptionsof cause and effect,were highlightedto show ‘impactpathways’.Second,the activitieswereprioritisedand sequencedtoallowforfuture uncertainty,whereby‘noregrets’activitieswere carriedoutfirst,andmore riskyor irreversible activitiesweredelayed.FromaRAPTA perspective,thissequencingof activitiesinthe implementationpathwayallowedflexibilityto be builtintothe projectdesign,andtominimise the riskof introducinganactivitywhichwaspotentiallymal-adaptive. Key issue Impact Impact Impact Direct impacts Impact Impact Impact Indirect impacts Impact Impact STEP 1 IMPACTSSTEP 2 CAUSES Cause Cause Cause Cause Cause Cause Cause Cause Cause Indirect causes Direct causes STEP 3 FEEDBACK LOOPS 1 2 3 STEP 4 INTERVENTIONS TO BREAK VICIOUS CYCLES AND TACKLE CONTROLLING VARIABLES + _ Note: positive (+) feedbacks AMPLIFY, negative (-) feedbacks DAMPEN

- 13. 13 3 Vietnam case study 3.1 System Description Membersof CERDA ledthe discussionandpresentationof the systemdescription. The focusof thiscase studywas the Tay, Nung,HmongSan,Diu, Dzao,San Chi,Caolan,Hoa andKinhethnicgroupsfromThai NguyenProvince,whichis amountainousareainnorthernandcentral Vietnam.The communitiesare the poorestandmost vulnerablegroupsinVietnam.Recently,the targetcommunitieshave beensuffering fromthe impactsof climate change anduncertainlivelihoods,anddespite governmentsupporttheyhave not beenable toovercome theirproblems.Negativeimpactsof climate change include changeable weather,damagingextremesof hotand cold, andunseasonal rainfall. Forestdegradationanddeforestation isalsoimpactingthe communities’ livelihoods,since watergenerated fromthe native forestsisdeclining, andforestproducts (i.e.timberandnon-timberforestproducts) have beenexhausted.Asaresulttheyhave toinvestmore inagricultural production,whichdependsonwater availability. Asaconsequence almostall households mustborrow moneyfrom governmentbanks,andonly generate sufficientincome topay backthe interestratherthanthe loan. In 2012, Vietnamhad13.8 millionhaof forestscategorizedintospecial use forest,protectionforestand productionforest.The ManagementBoardof ProtectedForest(MBPF) andState Forestsown30% of the forestarea,while 16%is unallocatedand remains underthe managementof the CommunistPeoples Committee (CPC) throughlocal authorities. Forestunderthe managementof MBFPand the temporary managementof CPC isdegradedanddeforestedbecause itlacksthe effectiveinvolvement of local communities wholive nearanddependonthe forests.The ForestProtectionand DevelopmentPlanfor 2011-2020 statesthat managementboardsof special use andprotectionforests shouldinitiate co- managementmechanismswithlocal communities toshare responsibilitiesforforestprotection, developmentand mutual benefits.Ethnicminoritieswith traditionalknowledge andcustomarygovernance can make significantcontributionstothe preventionof deforestation, andhence contribute toboth climate mitigationandadaptation. Withthe supportfrom a projectconductedbyCERDA, the case study communitieshave beenallocated publicforestlands,andtherefore have the use rightsfor50 years.The CERDA projectisalsobuilding capacity(technical,legal,governance andmanagement), andpromotingthe institutional development of the target communities whichensuresthattheyhave legal entitiesand are able tofunction as the forest owners.They are alsoadaptingto and mitigatingthe impactsof climate change byprotectingthe natural forestthroughcollectiveaction.After 2yearsof protection,the natural forest isalreadyprovidingbetter watersupplies forcrops,allowingdiversificationoutof agriculture andreducedincidence of landslidesand flooding. Traininginbusinessmanagementhasalsoenabledcommunitiestoearnmore income fromforest products,including REDD+schemes.

- 14. 14 Native forests in Thai Nguyen Province, Vietnam (Wikipedia) 3.2 System Assessment The case studygroup identifiedandrankedthe followingkeyissues: 1. Unstable agricultural production 2. Poorcommunityaccessto forestlandand resources 3. Limitedmarketaccessforlocal produce 4. Limitedcommunityaccessandinfluence onstate policies 5. Genderinequality 6. Limitedcommunitypowerindecision-makingthroughpoorparticipation 7. Poorcommunityaccessto publicinformationandtechnology 8. Decliningrespectfortraditional knowledge The group’scausal loopanalysisfocussedonthe primaryissue,unstableagriculturalproduction (Figure3). Notably,manyof the otherissueslistedemergedasdirector indirectcauses,withthe exceptionof market access forlocal produce (althoughthiswasaddressedbythe interventions),genderinequalityanddeclining respectfortraditional knowledge. There werefourdirectimpacts:abandonmentof agricultural land,less food,unstable andlessincome,andincreasedagriculturalinputs. Thisledtoillegal logging,urban migration,poverty,anddebtburdenstobanksand blackmarketlenders, andultimately children with motherlessfamilies.Directcauseswere extreme weathereventsandreducednatural watersuppliesfrom the forests.Indirectcauseswere conversionof natural forest,forestdegradationandillegal logging,which inturn were drivenbyimproperlanduse planningandpolicy, andlimited communityparticipation and access to forests.Two positivefeedbackloopswere identified.First,illegalloggingexacerbatedthe reductioninwatersuppliesfromthe forest.Second,increasingpovertyfurtherreducedcommunity participationinforestplanning. The interventionswere:1.Allocation of publicforestlandsto local ethnic groupsto be managed under successfultraditionalpracticesthrough co-managementwith government;2.Achieving legal statusof communities;3. Capacity-building forcommunitiesand stateagencies;4. Alternativeincomegeneration activities (e.g.organicproduce,newmarkets). These all aimedtotackle the viciouscyclescausedbythe feedbackloops,andthe indirectcausesof illegal loggingandlimitedcommunityaccesstoforests,plus weaklandpolicyenforcementandlowcommunityparticipationinforestmanagement.

- 15. 15 Figure 3. The causal loopanalysisforthe primaryissue inthe Vietnamcase study,unstable agricultural production.Interventions(stars) were:1. Allocation of public forestlandsto local ethnic groupsto be managed undersuccessfultraditionalpracticesthrough co-managementwith government;2.Achieving legal statusof communities;3. Capacity-building forcommunitiesand stateagencies;4. Alternativeincome generation activities (e.g.organicproduce,new markets) Unstable agricultural production Abandonment ofagricultural land Unstableand lessincome Direct Urban migration Increasing poverty Indirect Illegallogging IMPACTSCAUSES Reducedwater fromforest Extreme weather events Lossofnatural forest Naturalforest degradation Conversionof naturalforestto agricultureand plantations Illegallogging IndirectDirect Increasing debtburden tobanksand blackmarket + + Improperforest landplanning Weakland policy enforcement Lowcommunity participation Limited community accessto forestland Lessfood Increased agricultural inputs Motherless children 1 2 3 4

- 16. 16 3.3 Options and Pathways In thissession the groupdesignedan‘implementationpathway’forthe mostimportantintervention: Allocation of public forestlandsto local ethnic groupsto be managed undersuccessfultraditionalpractices through co-managementwithgovernment.Activitiesweresequencedovertime tofollow alogical chain, but alsoto avoidcommittingtoactionswhichmightprove maladaptiveora waste of resourcesif sudden shockswere to occur (Figure 4). For example,the grouprecognised thatestablishingFree andPrior InformedConsentwithtargetcommunitieswasessential before certificatesof ownershipcouldbe issued. However,some engagementwithgovernmentwasnecessaryearlyinthe process,since withouttheir approval furtherprogresswas futile. The Vietnam case study group conducting their casual loop analysis for unstable agricultural production (UNDP)

- 17. 17 Figure 4. The implementationpathwayforthe Vietnamcase study’smostimportantintervention, Allocation of public forestlandsto local ethnic groupsto be managed undersuccessfultraditionalpractices through co-managementwithgovernment.Activitiesare sequencedovertime tomaximiseflexibilityunder future uncertainty. Goal 1.Allocationof publicforestlands tolocalethnic groupstobe managedunder successful traditional practicesthrough co-management withgovernment Draft innovative modality procedure offorest allocation SetupFree andPrior Informed Consent (FPIC) Teams Organise community meetingsto introduce idea Approval from government authorities TIME Draftforest management planfor consultation Draft community convention onforest protection Setup Village Technical Teamfor fieldwork Training FPICTeams Training Village Technical Team Conduct FPICatsub- villagelevel Implement fieldwork byVillage Technical Team Cluster villages basedon traditional relationships Implement in-door activitiesby experts Government issues certificateof ownershipto communities

- 18. 18 4 Nepal case study 4.1 System Description Membersof CIPRED ledthe discussionandpresentationof the systemdescription. The focusof thiscase studywas the Gorung,Tamang, Magar and Dura ethnicgroupsinthe LamjungRegionof Nepal,which liesin the middle of the countryand spanstropical to trans-Himalayanecosystems.Indigenouspeoplescomprise 35% of the total populationof Nepal,andtheyhave aclose relationshipwithforestsandnatural resources. Forestsunderpintheirlivelihoods,andtheircultural,traditionalandspiritual values.Althoughthe Governmentof Nepal has recognized59Indigenous groupsandvotedforthe UnitedNationsDeclaration on the Rightsof IndigenousPeoples,there have beennoinitiativesbythe governmenttoaddress Indigenousrightsandtosupportthe continuedpractice andprotectionof theirtraditionalknowledge to manage forests,ecosystemsandbiodiversity.Consequentlymanygovernmentpolicies,particularlyforest regulations,climate change policiesandprogramsare not inline withtheirinternational obligationsand agreements. The impactsof climate change are highlyvisible amongstIndigenouscommunitiesinNepal,who have dependedupon subsistence farmingandnatural resourcesforgenerations.Theirwatersourcesare drying up and rainfall patternsare changing,resultingin longerdryseasonsandintense rainfall.Snow andglacier meltisaccelerating,causing floodingandlandslides.Indigenouspeopleshave beenprotectingand managingforests,waterresources, ecosystemsandbiodiversity,andtheirtraditional knowledge and cultural practices couldcontribute tothe sustainable managementof natural resources.However,they require supporttoapplythese skills,andalsoto buildtheirownresilienceto climate change. For the Magar and Dura ethnicgroups,climate change ishavingnegativeimpactsontheiragricultural productionandanimal husbandry.Also,bymanagingnative forests usingtraditionalknowledge,theyhave protectedwaterresourcesbothfordrinkingwaterandfarming,notonlyfortheircommunitiesbutalsofor the neighbouringvillages.Due tothe lengtheningdryseasonandforestfire,watersourcesare declining, and highlyendangeredspeciesare disappearingfromthe forests. CIPRED hasbeen workingwithDuracommunitiesinSindhure andNetaVillage DevelopmentCommittees in LamjungDistrictto protectmore than 1000 ha of forest. CIPREDhasworkedbothat local and national levelstocoordinate activitieswithconcernedgovernmentagencies, suchasthe Ministryof ForestandSoil Conservation andthe Ministryof Environment,Science andTechnology.More recentlyCIPREDhasbeen developingaprogramfor emissionsreductionsincoordinationwith the Nepal Federationof Indigenous Nationalities, Federationof CommunityForestryUsers'Group,RastriaDalitNetworkandothers. Asa result,governmentagencies have committedsupport forIndigenouspeoples toensure theirrightsforthe sustainable management of forests andlivelihoods,movingtowardsapolicyforIndigenousPeoples' Sustainable Self-determinedDevelopment.

- 19. 19 The mountainous Lamjung Region of Nepal (Dmitry A. Mottl) 4.2 System Assessment The case studygroup identifiedandrankedthe following 16 keyissues: 1. Water scarcity 2. Forestfires 3. Landslidesandsoil erosion 4. Recognitionof landownershiprightsforIndigenouspeoples 5. Changesinseasonsandweatherpatterns 6. Changesincroppingpatterns 7. Urban migration 8. Low level of women’sparticipationindecision-making 9. Lack of native species’ seed 10. Foodinsecurity 11. Illegal logging 12. Corruptioninlocal andnational government 13. Lack of transparencyinaccessto fundingforIndigenouspeoplesandwomen 14. Limitedmarketaccessforsale of local produce 15. Lack of shelterhomesfornatural disasters 16. Lack of road and electricityinfrastructure The group’scausal loopanalysisfocussedonthe primaryissue, waterscarcity (Figure 5). Several of the otherissueslistedemergedasdirector indirectcauses andimpacts,withthe exceptionof landslidesand soil erosion,women’sparticipationindecision-making, marketaccessforlocal produce,lackof transparencyforfunding,shelterhomesandroadandelectricityinfrastructure.

- 20. 20 There were five directimpacts:lowagriculturalproduction, abandonmentof agricultural land, decreasing drinkingwatersupplies,drycropsandvegetation,andconflictoverwaterdistribution. Thisledtofood insecurity, urbanmigration,sanitationandanimal husbandryproblems,forestfiresandsocial disunityand disharmony.Inaddition,foodinsecurityencouragedurbanmigration. Directcauseswere deforestation, introductionof water-intensive crops,inappropriateforestrypolicies,norecognitionof traditional governance,andchangesincroppingpatternsandthe use of inorganic inputs. Indirectcauses were illegal logging,whichwasfuelledbycorruption,decliningnative speciesandvegetation,conflictingwatershedand forestpolicies,andtemperature increasesandlongerdryseasonscausedbyclimate change. Three positive feedbackloopswere identified.First, foodinsecuritywasdrivingchangesincropping patternsand the use of inorganicinputs.Second,forestfireswere exacerbatingincreasingtemperatures and longerdryseasons.Third,forestfireswere alsoacceleratingthe decline innative vegetationspecies. The three interventions identified were:1. Strengthen traditionalknowledgeand practicein natural resourcemanagementand land use;2. Introduceorganicfarming and climate resilient crops;3. Reforestation using nativespecies. The firsttwotargetedthe linkedindirectanddirectcausesof water scarcity,temperature increasesandlongerdryseasonscausedbyclimate change andresultingchangesin croppingpatternsandthe use of inorganicinputs.The third tackledthe viciouscycle causedby forestfires acceleratingthe declineinnative vegetation.

- 21. 21 Figure 5. The causal loopanalysisforthe primaryissue inthe Nepal case study, waterscarcity. Interventions(stars) were:1. Strengthen traditionalknowledgeand practicein naturalresource managementand land use;2. Introduceorganicfarming and climateresilient crops; 3. Reforestation using nativespecies Waterscarcity Low agricultural production Decreasing drinkingwater supply Direct Urban migration Sanitation problems Indirect Foodinsecurity IMPACTSCAUSES Inappropriate forestrypolicy Deforestation Corruption Declining nativespecies andvegetation Illegallogging Conflicting forestand watershed policies IndirectDirect Forestfire + +Temperature increaseand longerdry season Abandoned agricultural land Drycropsand vegetation 2 3 Conflictover water distribution Social disunityand disharmony Animal husbandry problems Introductionof waterintensive crops Norecognition oftraditional governance Changesin cropsand inorganic inputs + + 1

- 22. 22 4.3 Options and Pathways In thissessionthe groupdesignedanimplementationpathwayforthe mostimportantintervention, Strengthen traditionalknowledgeand practicein naturalresourcemanagementand land use.First,the groupdevelopedtheirTheoryof Change,whichhadthe ultimate goal of reducingwaterscarcity(Figure 6). Thisshowedthree impactpathwayswithinthe Theoryof Change:one relatedtopolicyadvocacyand lobbying,asecondrelatedtore-plantingof native speciesandreducingfireforecosystemhealth,anda thirdrelatedtorestorationof watersourcesandrainwaterharvesting.Next,they sequenced activitiesfrom the Theoryof Change over5 years to followalogical chain,butalsotoavoidcommittingtoactionswhich mightprove mal-adaptiveora waste of resourcesif suddenshockswere tooccur (Figure 7). Forexample, the group recognised thatestablishingrainwaterstorage andrainwaterharvestingwasonlyfeasible in Years 3 and 4 afterfoundational researchhadbeencompletedinYear1. The Nepal case study’s casual loop analysis for water scarcity (UNDP)

- 23. 23 Figure 6. The Theoryof Change forthe Nepal case study’smostimportantintervention, Strengthen traditionalknowledgeand practicein naturalresourcemanagementand land use,withthe goal of reducing waterscarcity.There were three ‘impactpathways’:policy advocacyandlobbying(purplearrows),re- plantingof native speciesandreducingfire forecosystemhealth(greenarrows),andrestorationof water sourcesand rainwaterharvesting(orangearrows).

- 24. 24 Figure 7. The implementationpathwayforactivitiesinthe Nepal case study’smostimportantintervention, Strengthen traditionalknowledgeand practicein naturalresourcemanagementand land use,withthe goal of reducingwaterscarcity.Activitiesare sequenced overtime tomaximiseflexibilityunderfuture uncertainty.

- 25. 25 5 Nicaragua case study 5.1 System Description Membersof CADPI ledthe discussionandpresentationof the systemdescription. The focusof thiscase studywas the Miskitu ethnicgroupfromHaulover,IndigenousTerritoryof PrinzuAwal Un,locatedonthe Caribbean seaboardof Nicaragua(Figure 8).Thisregionhasthe highestratesof povertyinthe country, withlowlevelsof educationandhealthservices.LandisownedcollectivelywithinanIndigenousTerritory, whichisgovernedbya board of communitymembers.Communitieshave amodel of self-determination basedon national laws.Nationally,33%of the country’sarea isdemarcated and titledinthe name of the Indigenous communities. The Miskitucommunity’slivelihoodsare based onfisheries,butstocksare beingdepleteddue to overfishingbyindustrialfisheries. Forexample,coastal shrimpfisherycatcheshave droppedby42% between2003 and 2014. Lobsters,queensnailsandseacucumbersare the most valuable marine resources.Agriculture andthe extractionof pine woodare otherimportanteconomicactivitiesforthe community. Climate change impactsare alsoevident,withcoastal erosioncausedbysealevel rise,and extendeddryseasonswhichencourage firesinthe surroundingpine savanna. Extremerainfall eventsand floodingare alsobecomingmore frequent. CADPIisan Indigenouscommunityorganizationwhichsupportsthe twoethnicgroupsinthe Indigenous Territoryof PrinzuAwal Un: the Miskituand Mayangna. At the communitylevel CAPDIprovidestrainingon climate change issues,communityreforestation,IndigenousTV andradiocommunication,agricultural productionwithafocus onfoodsecurityas a formof adaptationtoclimate change,wood-burningstoves, and supportingterritorialgovernance.Forexample,CAPDIhasbuiltcommunitymapsinhighrelief (3D) to assistcommunitynatural resource andlivelihoodplanningprocesses. CAPDIhave alsosupportedthe traditional use of pine savannas, mangroves andcoral cays, pluspromotingthe role of womeninfisheries. CAPDIalsoacts as a brokerforcommunitiesindiscussionswiththe national governmentonfishery,climate change and governance issues.

- 26. 26 Figure 8. Haulover(circled),locatedonthe Caribbeanseaboardof Nicaragua A coastal community in Haulover, Nicaragua (CADPI)

- 27. 27 5.2 System Assessment The case studygroup identifiedandrankedthe followingkeyissues: 1. Coastal erosionfromsealevel rise,and resultinglossof soil andvegetation 2. Increasingsalinityinfreshwaterwells,affectingaccesstowater 3. Low state investmentinhealth,education,securityandotherbasicservices 4. Depletionof mangrovesdue toharvestingforfirewood 5. Depletionof natural resourcesdue tosavannafiresandflooding 6. Gastro-intestinal disease 7. Disabilitiesamongstdivers 8. Social impactsof the narcoticeconomy The group’scausal loopanalysisfocussedonthe primary issue,coastal erosion(Figure 9).Asforthe other case studies,manyof the otherissueslistedemergedasdirectorindirectcausesandimpacts,butinthis case withthe exceptionof disabilitiesamongstdiversandthe social impactsof the narcotic economy. There were three directimpacts:lossof vegetation, lossof soil andland,andsalinizationof freshwater wells. Thisledto a reductioninfishstocksandbiodiversity,sedimentation,decliningagriculture andlinked foodsecurity,lesslandforhousing,gastro-intestinal diseases,andwaterscarcity.These ledalsoto a lackof jobopportunitiesandurbanmigration,plussocialdisunityandconflict. Directcauseswere lackof awarenessof climate change amongstthe community,erosivewaves,flooding,deforestation andsand extraction. Indirectcauses were lowlevelsof educationamongstthe community,sealevel rise, more intense hurricanes,weakIndigenousterritorial institutions andlinkedintensive extractivepractices, povertyandthe needforcash. Two positive feedbackloopswere identified.First, the depletionof fishstockswaspromoting intensificationof extractivepractices,andparticularlysandextractionanddeforestation. Second, alackof jobopportunitiesforthe local communitywasdrivingpovertyandaneedforcash,whichin turnwas causingsandextractionanddeforestation. The five interventionsidentified were:1. Strengthen naturalresourcemanagementnorms;2.Enforce traditionalregulations; 3. Incomegeneration activitiesand fishery diversification; 4. Reforestation, and5. Coastalprotection.The firstfourtackledthe feedbackloop andinteractionsbetweenweakIndigenous territorial institutionsandintensiveextractive practices,povertyandthe needforcash,anddeforestation and sandextraction. The fourthwasa directresponse tosealevel rise andresultanterosive waves. 5.3 Options and Pathways In thissessionthe groupdesignedan implementationpathwayfortheirinterventions.The group developedtheirTheoryof Change,whichhadthe ultimate goal of reducingcoastal erosion(Figure 10).This showed five ‘impactpathways’withinthe Theoryof Change: one relatingtocommunityandstakeholder mobilisation,asecondformobilisingandrecordingtraditional knowledge,athirdforreforestationof mangroves,coconutsandpine forest,afourthfor rainwaterharvesting,andafifthforcoastal protection. Ratherthan draw a separate implementationpathway,the grouporderedthe activitiesintoasequence that wouldprovide necessarysocial and institutional preparation,andalsotomaximiseflexibilityunder future uncertainty (Figure10).The firstkeystepwas to establishFree andPriorInformedConsentfromthe community,followedbyorganisingcommunitysectorsandengagingwithexternal stakeholders.The final, mostriskyactivity,constructingartificialreefsandcoastal protection,wasthe lastto be implementeddue to the significantlevel of irreversibilityand‘sunk’costs.

- 28. 28 Figure 9. The causal loopanalysisforthe primaryissue inthe Nicaraguacase study,coastal erosion. Interventions(stars) were:1. Strengthen naturalresourcemanagementnorms;2.Enforcetraditional regulations;3. Incomegeneration activitiesand fishery diversification; 4. Reforestation;5.Coastal protection

- 29. 29 Figure 10. The Theoryof Change forthe Nicaraguacase study’sinterventions,withthe goal of reducing coastal erosion.There were five ‘impactpathways’: communityandstakeholdermobilisation (purple arrows), traditional knowledge (blue arrows), reforestation (greenarrows),rainwaterharvesting(brown arrows),andcoastal protection(orange arrows).Activitiesare orderedbynumberintoanimplementation pathway,wherebytheyhave beensequencedovertime tomaximise flexibilityunderfuture uncertainty.

- 30. 30 The Nicaragua case study group’s casual loop analysis for coastal erosion (UNDP)

- 31. 31 6 Kenya case study 6.1 System Description Membersof ILEPA ledthe discussionandpresentationof the systemdescription. The focusof thiscase studywas the Maasai ethnicgroupfromNarok andKajiadoCountiesof Kenya. Pastoralistcommunities, includingthe Maasai, have beenclassifiedbyinternational andregional mechanismsasIndigenousPeoples. However,indicators forlifeexpectancy,school enrolmentandthe HumanDevelopmentIndex are farlower and povertylevelsfarhigheramongstpastoralists,withpovertylevelsaveraging70% comparedto a national average of 47%. YetKenya’snational livestockherdproducesupto12% of the country’sGDP, and Kenya’sdrylandscarry over60% of the country’slivestockpopulation.The beef sectorisrankedasone of Kenya’sfastestrisingeconomicsectorswithmeatconsumptionincreasingbynearly10% inthe past 6 years,withsteadygrowthprojectedoverthe comingyears.Policyandinstitutional bottle-necksare key constraintstothe developmentandsustainablemanagementof livestockinKenya,coupledwith poorroad conditions andhightransportcosts.Hence there isgreat potential forsome of the poorestIndigenous pastoralistcommunitiesinKenyatodevelopthroughimprovedlivestockmanagement,butthere are significantsocial andeconomicimpedimentstorealising this. Climate change presentsasignificantandgrowingchallenge toachievingsustainablerangeland managementandthe humandevelopmentof Indigenouspastoralists. Approximately85% of Kenya’sland area isclassifiedasaridandsemi-arid.Inmany areas,rainfall hasbecome irregularandunpredictable, extreme andharshweatherisnowthe norm, and some regionsexperience frequentdroughtsduringthe longrainyseasonwhile othersexperience severe floodsduringthe shortrainyseason.The 2010-2011 Horn of Africadroughtcrisisdemonstratedhowvulnerable Kenyaistoclimate change,andthisiscompounded by local environmental degradation,primarilycausedbyhabitatlossandconversion,pollution, deforestationandovergrazing.Pastoralistareasare particularlyvulnerabletothe impactsof climate change.Extendedperiodsof droughterode livelihoodopportunitiesandcommunityresilience,leadingto undesirablecopingstrategiesthatdamage the environmentandimpairhouseholdnutritionalstatus, furtherundermininglongtermfoodsecurity. Sustainable pastoralismisamulti-functional livestockmanagementsystemwhichcanprovide ecosystem servicesthatextendwell beyondthe boundariesof the rangelands,while maintainingsoilfertilityandsoil carbon,water regulation,pestanddisease regulation,biodiversityconservationandfire management. Rangelandshave apotential tosequesterbetween200and 500 kg of carbon perha annually,playingakey role inclimate change mitigation.Atthe heart of the environmental sustainabilityof pastoralismisadaptive managementbasedonthe Maasai’slocal knowledge,culture andinstitutions. However, pastoralistsface manifoldpressuresontheircommunitiesandlifestyle.Theseinclude droughtandotherdisastersbrought aboutby natural hazards andadvancingclimate change,localisedandcross-borderconflictandviolence, cattle rustling,cross-borderincursions,the exploitationof natural resourcesandshrinkingareasof landto range over.Whenadaptive migrationisnolongerpossible andcopingcapacitiesare largelyexhausted,the resultisforceddisplacement.The lossof traditionalgrazinglandtoprivatisationandlandsalesalso increasesthe riskof conflictwhendroughtsoccur,because itmakes dwindlingresourcesscarcerand interfereswithmigrationroutesbothwithinandacrossinternational borders. ILEPA aims to enhance environmental conservationandlivelihood diversificationforpastoralistIndigenous communities.ILEPA isanactive brokerat the community,county, nationalandinternational level,andhas cultivatedagoodworkingrelationshipwithactorsacrossthese levels.Conservation,climate change adaptationandIndigenousknowledge systems are ILEPA’skey strategicfocii. ILEPA isfoundermemberand servesasone of the technical advisorstothe IndigenousPeoplesNational SteeringCommitteeonClimate Change and REDD+.

- 32. 32 Maasai herder and livestock in Narok and Kajiado Counties, Kenya (ILEPA) The Kenya case study group discussing the key issues (UNDP)

- 33. 33 6.2 System Assessment The case studygroup identifiedandrankedthe following 10 keyissues: 1. Droughtand famine,plusfloods 2. Weakpoliciesandlawsrelatingtopastoral practices 3. Land fragmentation 4. Land-grabbingand selling 5. Inadequate basicsocial services(e.g.healthcentres,veterinaryservices) 6. Weakpolitical voice andrepresentation 7. Poormarket access 8. Weakgovernance systemsincountyandnational government 9. DisregardbymainstreamgovernmentforIndigenousknowledge systemsandpractices 10. Natural resource-relatedconflictandinsecurity The group’scausal loopanalysisfocussedonthe primaryissue, famine(Figure 11).Asfor the othercase studies,manyof the otherissueslistedemergedasdirectorindirectcausesandimpacts,butin thiscase withthe exceptionof poormarketaccess. There were six directimpacts:lackof water,migration,lossof cattle,weakenedcattle,lossof life andfood insecurity. Thisledtoacomplex webof linkagestoindirectimpacts:disruptionof social order,children droppingoutof school,social conflictoverlimitedresources,increasedhuman-wildlife conflict,increased dependencyonpoorstate services,lessincomeanda particularimpactonwomen. Directcauseswere drought,restrictionsoncross-bordermovementsof peopleandcattle,limitedlivelihoodopportunities, constrainedaccesstowater,and poor pasture management.There were overlappingandmultiple linksto indirectcauses:climate change,landfragmentation,landgrabbingandsale,weakpoliciesandlaws,a disregardforIndigenousknowledge,andthe breakdownof cultural norms. Two positive feedbackloopswere identified.First,the disruptionof social orderresultingfromfamine drivesfurtherbreakdownof cultural norms,whichexacerbatesseveral directcausesof famine,causinga viciouscycle. Second, migrationinresponsetofamine encourageslandgrabbingandlandsales,which furtherlimitslivelihoodopportunities,accesstowaterand poor rangeland management. The four interventionsidentifiedwere:1. Restore and strengthen culturalnormsand Indigenous knowledge;2.Policy advocacy; 3. Droughtearly warning system; 4.Enhanced accessto livestockmarkets and veterinary services.The first, priorityinterventionaddressed the feedbackloopandinteractions between the disruptionof social orderresultingfromfamine andthe breakdownof cultural norms.The secondaddressedthe feedbackloopinvolvingmigration,weakgovernmentpoliciesandlawswhichdrive landgrabbingand sale,andresultingrestrictionsoncross-bordermovements,limitedlivelihood opportunities,constrainedaccesstowaterandpoor pasture management.The thirdtackledthe increasing incidence of drought,andthe fourth aimedtoimprove livelihoodopportunities. 6.3 Options and Pathways In thissessionthe groupdesignedan implementationpathwayfortheirinterventions. First,the group developedtheirTheoryof Change,whichhadthe ultimate goal of reducingthe incidence of famine(Figure 12). This showedfour‘impactpathways’withinthe Theoryof Change:one relatingto improvingpasture, waterand livestockroutes;asecond todevelop earlywarningsystems anddisasterpreparedness; athird to strengthenIndigenousknowledge andgovernance of natural resource management,includingpolicy advocacy, and a fourthfor enhancingaccesstolivestockmarketsandveterinaryservices.The groupthen orderedthe activitiesintoa 5 yearimplementation pathway thatwould firstprovidenecessary preparation, and thenimplementinfrastructural andpolicychange (Table 1).

- 34. 34 Figure 11. The causal loopanalysisforthe primaryissue inthe Kenyacase study,famine.Interventions (stars) were:1. Restoreand strengthen culturalnormsand Indigenousknowledge;2.Policy advocacy;3. Droughtearly warning system;4. Enhanced accessto livestock marketsand veterinary services. .

- 35. 35 Figure 12. The Theoryof Change forthe Kenyacase study’s five interventions,withthe goal of reducing the incidence of famine.There were four‘impactpathways’:improvingpasture,waterandlivestockroutes (purple arrow);developingearlywarningsystems anddisasterpreparedness (blue arrow);strengthening Indigenousknowledgeandgovernance of natural resource management andpolicyadvocacy(green arrow);enhancingaccessto livestockmarketsandveterinaryservices (orangearrow).

- 36. 36 Table 1. The 5 yearimplementationpathwayforthe Kenyacase study,withthe goal of reducingthe incidence of famine Activities 1 2 3 4 5 1. Scoping research 2. Research, document and disseminate Indigenous knowledge systems and customary governance related to natural resource management through a knowledge-sharing platform 3. Build pastoralists' capacities and put in place pasture management and storage infrastructure 4. Train pastoralists in early warning system (EWS) technology 5. Create awareness and promote implementation of policy issues related to pastoralism and land tenure systems and accountability mechanisms6. Establish the EWS infrastructure 7. Build water harvesting infrastructure including surface water run- off dams, boreholes, roof-water 8. Delineate livestock routes to pasture, water-points and saltlicks 9. Train pastoralists on livestock market dynamics and establish the infrastructure to enhance access to livestock markets and veterinary services10. Establish dialogue platforms to build experience and knowledge- sharing between institutions related to pastoral systems 11. Enhance regional cooperation on cross-border pasture access strategies Project duration (years)

- 37. 37 7 Conclusions and evaluation 7.1 Applying RAPTA to GCF Priorto the RAPTA workshop sessionsthe IndigenousPeoples’representativeshaddraftedconceptnotes for the GCF. These aimedtomeetthe GCF’ssix investmentcriteria: 1. Climate impactpotential(Potentialto achievethe GCF's objectivesand results) 2. Paradigmshiftpotential (Potentialto catalyzeimpactbeyond a one-off projectorprogram investment) 3. Sustainable developmentpotential (Potentialto providewiderdevelopmentco-benefits) 4. Needsof recipient (Vulnerabilityto climate changeand financing needsof therecipients) 5. Countryownership (Beneficiary countryownership of projectorprogramand capacity to implement the proposed activities) 6. Effectivenessandefficiency (Economicand financialsoundnessand effectivenessof theproposed activities) The GCF naturallyplaces primacy onclimate change issues. However,RAPTA tools enable asystems analysisof the linkagesbetween climateanddevelopment issues,andpotentiallytransformational interventions.Assuch,the SystemAssessment exerciseshelpedthe case studiesto investigate the GCF’s secondandthird criteriainmore depth:paradigmshiftpotential,andsustainable developmentpotential. A comparisonof the priority RAPTA interventionsidentifiedforthe fourcase studieswiththe initial GCF conceptnotesdevelopedpriortothe workshopshowedsome changes(Table 2). ForVietnamandNepal the GCF and RAPTA priorities were similar,withthe managementof publicforestsandstrengthening traditional forestmanagement,respectively.ForNicaraguathe emphasisalteredfromterritorial governance tostrengtheningcoastal natural resource management,andinKenyaasimilarshiftwas evidentforpastoralism. Inall case studiesthe RAPTA interventionswere more specificbecausethey targetedthe underlying directand indirectcausesof climate anddevelopmentproblems,theircomplex linkagesandrelated viciouscycles. Asaresult,of the 16 interventionsinthe fourcase studies,onlythree specificallyaddressedclimate change issues,andnone were priorities.These were:introduce organic farmingandclimate resilientcrops(Nepal,2nd priority);coastal protectionfromerosive waves(Nicaragua, 5th priority),anddroughtearlywarningsystemsinKenya(3rd priority). The RAPTA analysesnowprovide the case studies’representativeswithaclearerrationale andjustification for theirGCF conceptnotes,anda potentiallytransformational setof targetedinterventions.The draft implementationpathwaysalsoprovide alogical planforfuture programactivities thattake into considerationfuture uncertainty.However,itshouldbe notedthat these are initial results,andonly representthe viewsof the participants.Toconducta full RAPTA planningexercise, whichshouldincludethe otherimportant componentsonengagement, governance andlearning,amore comprehensive processis requiredwhichinvolvesawiderrange of stakeholdersandtheirknowledge,valuesandgoals overseveral days.This 1 ½ day exercise simplyaimedtodemonstrate some of the keyprinciplesof taking asystems perspective of climateanddevelopmentchallenges,andtoprovide the IndigenousPeoples’ representativeswithsome newprojectplanningskills.Asdescribedinthe nextsection,itappearsthat these objectiveswere achieved.

- 38. 38 Table 2. Draft GCF conceptnote objectivesdevelopedforthe fourcase studiespriortothe RAPTA workshop,andthe priorityinterventionidentifiedasaresultof the RAPTA exercise. Case study Pre-workshop concept notes Priority RAPTA intervention Vietnam Community ownership and co-management of Allocation of public forestlands to local ethnic forests between government and communities groups to be managed under proven to sequester carbon and promote adaptation traditional practices through co-management with government Nepal Awareness raisingon resilienceto climate Strengthening traditional natural resource change; capacity-buildingof Indigenous people management and knowledge and their traditional knowledgeand practices; alternativelivelihood development; information dissemination Nicaragua Strengthen territorial governanceand Strengthen coastal natural resource livelihoods to adaptto climatechange management norms Kenya Enhance resilienceof pastoralistlivelihoods; Restoration and strengthening of cultural facilitatean enablingenvironment for norms and practices of rangeland pastoralism;enhance knowledge generation management 7.2 Evaluation At the endof the workshop eachparticipantwasaskedtowrite a single statementaboutthe primary learningtheyhadderivedfromthe RAPTA exercise.A range of answerswere given: “I learned how to isolate the direct impacts from the indirect” “I learned there is a need to identify project risks and needs” “The RAPTA framework is quite helpful” “It is very important to know the vicious circle of problems, direct/indirect causes to address both indirect/direct impacts and end up with activities to implement and right interventions” “Need to prioritise the activities, but we also need to consider the uncertainty of futures and possible risk – especially for infrastructure or activity with higher risk. Need to have enough information, consultation, meetings to minimise risk and optimise higher impact to meet the goal” “My analytical and critical skills have deeply been enhanced and strengthened” “The project cycle and prioritisation of the needs of society” “I have learned key issues and how to give them priority based on the RAPTA framework” “I have learned a systems assessment and the feedback loops which determine what priority interventions to take” “I need to do more work on how to formulate plans in the context of climate change adaptation and mitigation”

- 39. 39 “RAPTA is like mathematics – with a formula,systemicway of doing things (system assessment) and a way of checking (feedbackloops).Theequation getscompleted when you areable to point outwhereyou should begin your intervention” “I can work in a different context, even if I don’t have expertise in one area/issue” “I now think in a different way” “RAPTA could be easy to use with communities – flexible methodology” “I learned a different methodology to better structure interventions” “Causal loop analysis to identify interventions” “Prioritise interventions/sequence activities keeping in mind uncertainty and changes in future conditions” “I’ve learned about finding key issues and challenges when designing a project, connecting direct and indirect impacts or causes, find out feedback loops and actions for a project to follow” “Very good training with logical framework – I will apply it in project design – I will use the tool to train others, especially local communities” “Prioritisation of activities through the Theory of Change” “Prioritisation of activities – change is not easy but we must do our best” “It really fits into the GCFstandardsin the sense that they were looking how the project affects the people” “The RAPTA will give you an immediate picture of what the project will be in relation to issues – it is also systematic” “RAPTA can be useful and can be integrated with other tools for projects (e.g. identification to design implementation)”

- 40. 40 8 References Burns,D. 2012. Participatorysystemicinquiry. IDSBulletin 43: 88-100. Butler,J.R.A., Busilacchi,S.,Posu,J.,Liviko,I., Kokwaiye,P., Apte,S.C.andSteven,A.2015. SouthFlyDistrict Future DevelopmentWorkshopReport.ReportpreparedbyCSIROOceansandAtmosphere,Brisbane,and the Papua New GuineaNational FisheriesAuthority,PortMoresby. 38 pp. CIFOR and SEI 2009. Multiple-scale Participatory Scenarios: Vision, Policies and Pathways. Centre for International Forestry Research and Stockholm Environment Institute. 22 pp. O’Connell,D.,Abel,N., Grigg,N., Maru,Y., Butler,J.,Cowie,A.,Stone-Jovicich,S.,Walker,B.,Wise,R., Ruhweza,A.,Pearson,L.,Ryan,P. and StaffordSmith,M. 2016. Designingprojectsinarapidlychanging world:Guidelinesforembeddingresilience,adaptationandtransformationintosustainable development projects.(Version1.0).Global EnvironmentFacility,Washington,D.C. 106 pp. Availablefrom: http://www.stapgef.org/the-resilience-adaptation-and-transformation-assessment-framework

- 41. 41 CONTACT US t 1300 363 400 +61 3 9545 2176 e [email protected] w www.csiro.au YOUR CSIRO Australia is founding its future on science and innovation. Its national science agency, CSIRO, is a powerhouse of ideas, technologies andskills for building prosperity, growth, health and sustainability. It serves governments, industries, businessand communities across the nation. FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CSIRO Land and Water Dr. James Butler t +61 7 3833 5734 e [email protected]